by the Night Writer

I saw a reference to “the Siege of Turin” the other day and it made me curious so I did a little research. The first challenge I faced was determining just which Siege of Turin I was looking for – the one when the Italians of the Piedmont allied with Spain against the French, or the one when the Italians allied with the Austrians and Prussians against France and Spain? In those moments, all the castles, ruins and battlements I’ve been seeing over the past six weeks, and all the recurring family names – Lombards, Savoys, Medicis, Habsburgs, Bourbons and more – suddenly coalesced into a clearer understanding of Europe for my American brain, an understanding that was obvious enough, but still somewhat elusive.

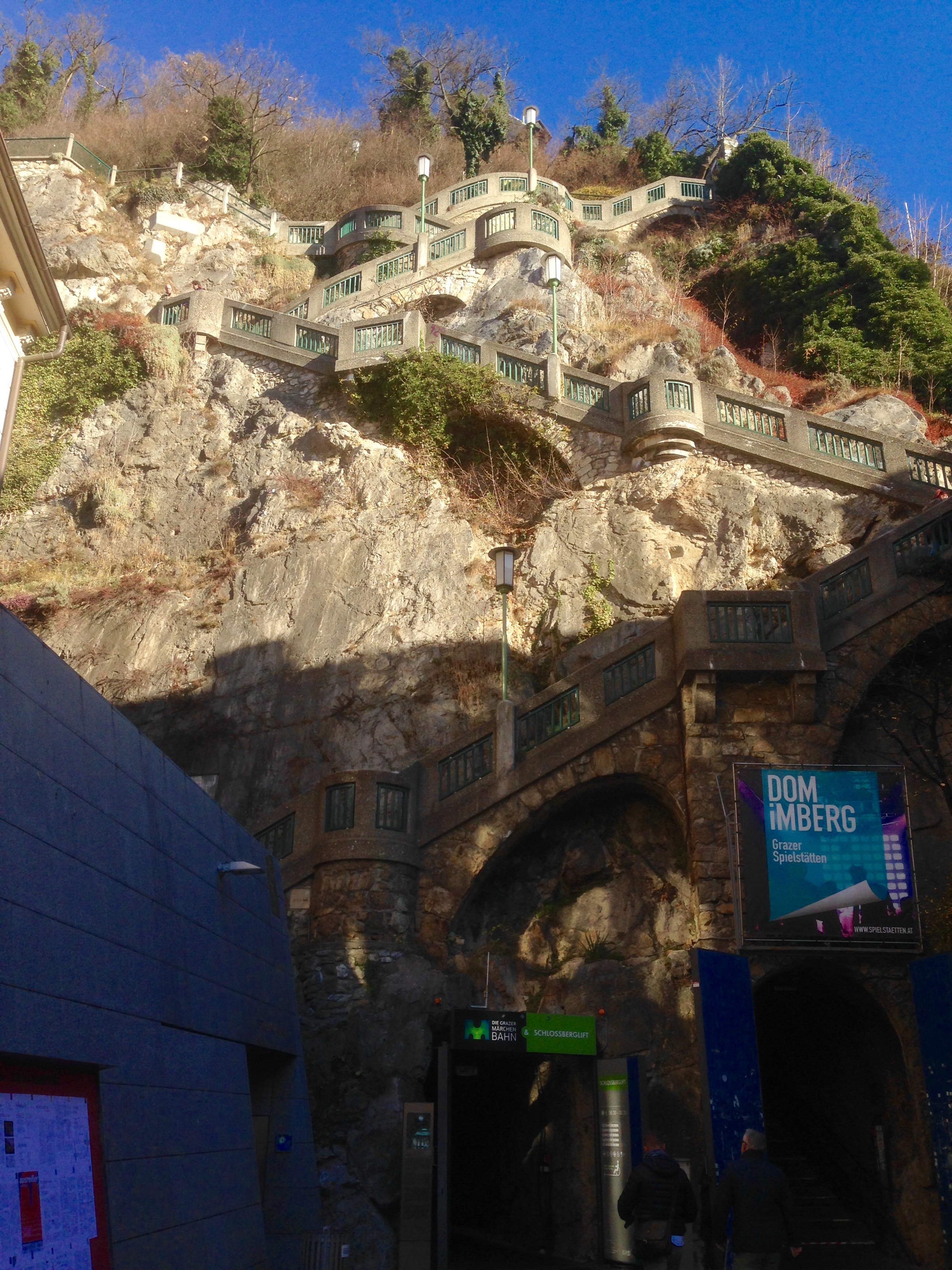

I have been trying to picture myself living in a Europe of past centuries, viewing the artifacts and architecture of nearly incessant hostilities and gamesmanship (driving through Austria there is another fortress on top of a hill every 3-4 kilometers) as power and influence waxed and waned throughout different regions . History and geography are literally stacked in heaps all around me, and in my fresh moment of clarity I began wondering what effect this living history might have on me if I were a European today. What does it do to one’s cultural sensibilities and view of the past and the future when there is a national memory of your neighbors camped outside your city walls, either bombarding you or trying to starve you out? It’s simply not something Americans have had to think about much. True, we had a Civil War, and fought natives for territory, and contended with European armies and navies, but the possibility of England landing a force on our shores and torching Washington, D.C. is almost unimaginable to us now. I wonder just how unimaginable – or imaginable – a similar episode might be for an Italian, a Belgian, a Pole?

For that matter, what connection might you feel to a country or a leader here? When I looked up the history of Trieste during our visit I discovered that the city has, by turns, been French, German, Austro-Hungarian, Slovenian and Italian. In a history of changing alliances, borders and affiliations, would you be loyal to a distant capital or to your region? Would you be an Umbrian or Piedmontese in Italy? Swear allegiance to Galicia or Catalonia rather than to Spain and Madrid? The “United States” is a something that’s been “normal” for Americans for some 240 years; we don’t think of Ohio invading Pennsylvania for its oil, or Wisconsin conquering Minnesota and making it illegal for anyone to be a Vikings fan. At least we haven’t since 1865, anyway, though there are still family stories of survival in the Civil War handed down in my family.

In Europe you don’t have to go back to the Siege of Turin or the “War of Spanish Succession”; within the last 100 years you’ve seen two world wars in which the Christian nations of the continent were at each other’s throats. In the Czech Republic, there are people alive today who well remember what it was like to live under both the Nazis and the Russian Communists, and who have seen tanks and machine guns in their streets. In Turin and Gratz, ancient tunnels under the city were still used as shelters from Allied bombs in WW2.

Is the EU now a natural and enlightened entity of common purposes across the nearly invisible borders of its member states, embraced by all, or is the connection more superficial? While we have had some conversations with “locals” in our travels, the language barrier challenges both revelation and nuance. Our Hungarian driver and tour guides were adamantly opposed to any possibility of the Communists returning, and nearly as outspoken about the influx of Muslim migrants. Our driver said that their greatest fear, though, is nationalism – more so among their neighbors, but also within their own country. The Hungarian prime minister, Viktor Oban, has been popular with the citizens for his tough, “strong man” talk, but our driver said there is great concern that he has lately been making overtures toward an apparent alliance with Vladimir Putin. In the Czech Republic I have read similar things about the Czech president, Milos Zeman. Both Oban and Zeman are vocal critics of the EUs embrace of migrants (both countries have all but closed their borders to refugees), and even countries such as Germany and Sweden which have welcomed more than a million refugees are showing strong internal dissent and resistance to the practice.

It can be a slow process of sorting your assumptions from your observations and trying to line up a new working model. We tend to think of Europe as staid and monolithic (at least in its politics). “Old” doesn’t mean “settled” though. The ancient conflicts here drove many emigrants to the United States. I’m not so sure that the underlying dynamics are that far removed. Making assumptions here is kind of like planting a garden here; it can be nice and even lovely – but don’t be surprised if someone comes tramping through it when you least expect.