My hand-writing is atrocious and I admit that with more shame than pride. I dutifully learned my printing and cursive writing styles in school, but my thoughts have always been faster than my hand. Trying to get them down in longhand is like trying to rein in a team of stampeding horses — when the horses are behind you. In their haste to keep up my fingers have often cut corners around the edges of some letters, or lapped over the lines meant to keep the letters inside, or sketched the first few letters of a word while giving the rest of the word a lick and a promise.

My hand-writing is atrocious and I admit that with more shame than pride. I dutifully learned my printing and cursive writing styles in school, but my thoughts have always been faster than my hand. Trying to get them down in longhand is like trying to rein in a team of stampeding horses — when the horses are behind you. In their haste to keep up my fingers have often cut corners around the edges of some letters, or lapped over the lines meant to keep the letters inside, or sketched the first few letters of a word while giving the rest of the word a lick and a promise.

Never better than mediocre at it’s best when I was younger and using it regularly, my hand-writing has deteriorated as I’ve gotten older, even though I still use it quite a bit. My generation still had to write most of our reports and essays in longhand while in school, and I didn’t take a typing class until my junior year in high school. I typed my college papers, except for my semester in England when I didn’t have access to a typewriter and had to turn in four large bluebooks of laborious cursive. You’d think I’d be able to keep my “hand” in these days since I take copious notes at work and fill roughly one notebook a year in scrawled highlights of sermons from church. My wife, however, looks at my notes and says that I write in tongues, and it is getting to the point now where even I can’t read the scratchings if it’s been a week or two since they were put down on paper.

My struggles are not unusual and, in fact, the generations behind me may be even worse off according to a recent article in the Boston Globe noting the decline in handwriting in the U.S., most likely due to a decline in teaching it as students and teachers conform to the ubiquity of the keyboard, even in the elementary grades.

To previous generations, clear and speedy handwriting was essential to everything from public documents to personal letters to generals’ orders in battle. As literacy became more widespread, various handwriting methods arose. There was italic, starting in the 15th century, and then in the 17th century came roundhand – called copperplate in the United States – seen in the Declaration of Independence and the script of Benjamin Franklin. In the 1820s, Platt Rogers Spencer developed the Spencerian script, which became the American standard in schools (it survives in the Coca-Cola logo).

Then came A.N. Palmer. While working as a clerk in Iowa in the 1880s, Palmer devised a way of writing that eliminated Spencer’s fancy curlicues and purportedly minimized fatigue, too. He promoted his method in a book, “Palmer’s Guide to Muscular Movement Writing,” and by 1912 his method was dominant in American schools. Palmer and its offshoots featured the odd large number 2 for the capital Q, the capital D with the little forelock, and the M and N that start with a loop.

However much you studied your Palmer, though, your “hand” was distinctive – as personal as your voice or laugh. But as typewriters proliferated after World War II, handwriting gradually became less important. Authors typed their manuscripts and students typed their school papers. As telephones became universal, letter-writing virtually disappeared. In the e-mail age, most people seldom need to write more than a grocery list or a short note, or sign a check. It’s not only kids; many who formerly wrote fluently and neatly have forgotten how.

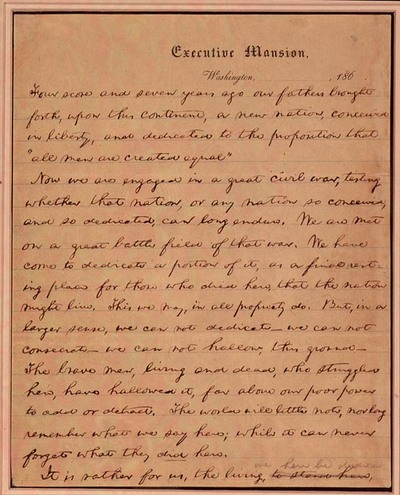

“It’s a very disturbing problem,” said Kate Gladstone of Albany, N.Y., who has a website specializing in handwriting improvement. “I see people in their 20s and 30s who cannot read cursive. If you cannot read all types of handwriting, you might find your grandma’s diary or something from 100 years ago, and not be able to read it.” There are practical concerns as well. Sometimes we don’t have a computer, or the professor won’t let us bring it to class to take notes. Or sometimes, as happened in New Orleans hospitals during Hurricane Katrina, computers lose power and medical orders and records have to be written out by hand.

In a way, it’s as if hand-writing has become another “dead” language like Greek or Latin. All three were once thought to be the foundations of a good education and now are the arcane province of “Men of Letters” (and Women).

While typing — whether on a typewriter, computer or hand-held device — is the most efficient and functional way to put words (or electrons) on paper these days, and despite my own struggles with the craft of penmanship, a part of me feels sadness at the decline of one of the “Three R’s”. There’s an elegance and classiness in being able to master a graceful note to a loved one or even a list of chores on the whiteboard stuck to the refrigerator door. Perhaps that’s why so many important documents today still affect a hand-written look. How ironic that a student today might not be able to read his or her diploma!