Martha Washington wrote a letter to a relative on the eve of her husband’s departure to the Convention in 1774:

PATRICK HENRY, on his return home from the first Continental Congress in 1774 was asked whom he thought was the foremost man in the group:

“Colonel Washington is unquestionably the greatest man on that floor.”

Abigail Adams first met Washington in 1774, and wrote to her husband:

You had prepared me to entertain a favorable opinion of him, but I thought the half was not told me. Dignity with ease and complacency, the gentleman and the soldier look agreeably blended in him. Modesty marks every line and feature of his face.

When George Washington was elected (unanimously) by the First Continental Congress to be Commander in Chief (this was in June, 1775) – here was the brief acceptance he made:

“Lest some unlucky event should happen unfavorable to my reputation, I beg it may be remembered by every gentleman in the room, that I this day declare, with the utmost sincerity, I do not think myself equal to the command.”

GEORGE WASHINGTON, writing to Martha on June 18, 1775, following his nomination as commander in chief:

My Dearest: I now sit down to write to you on a subject which fills me with inexpressible concern, and this concern is greatly aggravated and increased when I reflect upon the uneasiness I know it will give you. It has been determined in Congress that the whole army raised for the defence of the American cause shall be put under my care, and that it is necessary for me to proceed immediately to Boston to take upon me the command of it.

You may believe me, my dear Patsy, when I assure you, in the most solemn manner, that, so far from seeking this appointment, I have used every endeavour in my power to avoid it, not only from my unwillingness to part with you and the family, but from a consciousness of its being a trust too great for my capacity, and that I should enjoy more real happiness in one month with you at home than I have the most distant prospect of finding abroad, if my stay were to be seven times seven years.

But as it has been a kind of destiny that has thrown me upon this service, I shall hope that my undertaking is designed to answer some good purpose.

George Washington describes here what a general expects in his aides:

The variegated and important duties of the aids of a commander in chief or the commander of a separate army require experienced officers, men of judgment and men of business, ready pens to execute them properly and with dispatch. A great deal more is required of them than attending him at a parade or delivering verbal orders here and there, or copying a written one. They ought, if I may be allowed to use the expression, to possess the Soul of the General, and from a single idea given to them, to convey his meaning in the clearest and fullest manner.

GEORGE WASHINGTON, letter to Joseph Reed, early December, 1775, after a disappointing recruiting drive:

I have oftentimes thought how much happier I should have been if, instead of accepting the command under such circumstances, I had taken my musket on my shoulder and entered the ranks; or, if I could have justified the measure to posterity and my own conscience, had retired to the back country and lived in a wigwam. If I shall be able to rise superior to these and many other difficulties which might be enumerated, I shall most religiously believe that the finger of Providence is in it to blind the eyes of our enemies, for surely if we get well through this month it must be for want of their knowing the disadvantages which we labor under.

George Washington wrote the following on the eve of his inauguration in 1789:

It is said that every man has his portion of ambition. I may have mine, I suppose, as well as the rest, but if I know my own heart, my ambition would not lead me into public life; my only ambition is to do my duty in this world as well as I am capable of performing it, and to merit the good opinion of all good men.

David McCullough describes, in his book on John Adams, the first inauguration day:

On the day of his inauguration, Thursday, April 30 1789, Washington rode to Federal Hall in a canary-yellow carriage pulled by six white horses and followed by a long column of New York militia in full dress. The air was sharp, the sun shone brightly, and with all work stopped in the city, the crowds along his route were the largest ever seen. It was as if all New York had turned out and more besides. “Many persons in the crowd,” reported the Gazette of the United States “were heard to say they should now die contented – nothing being wanted to complete their happiness – but the sight of the savior of his country.”

In the Senate Chamber were gathered the members of both houses of Congress, the Vice President, and sundry officials and diplomatic agents, all of whom rose when Washington made his entrance, looking solemn and stately. His hair powdered, he wore a dress sword, white silk stockings, shoes with silver buckles, and a suit of the same brown Hartford broadcloth that Adams, too, was wearing for the occasion. They might have been dressed as twins, except that Washington’s metal buttons had eagles on them.

It was Adams who formally welcomed the General and escorted him to the dais. For an awkward moment Adams appeared to be in some difficulty, as though he had forgotten what he was supposed to say. then, addressing Washington, he declared that the Senate and House of Representatives were ready to attend him for the oath of office as required by the Constitution. Washington said he was ready. Adams bowed and led the way to the outer balcony, in full view of the throng in the streets. People were cheering and waving from below, and from windows and rooftops as far as the eye could see. Washington bowed once, then a second time.

Fourteen years earlier, it had been Adams who called on the Continental Congress to make the tall Virginian commander-in-chief of the army. Now he stood at Washington’s side as Washington, his right hand on the Bible, repeated the oath of office as read by Chancellor Robert R. Livingston of New York, who had also been a member of the Continental Congress.

In a low voice Washington solemnly swore to execute the office of the President of the United States and, to the best of his ability, to “preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.” Then, as not specified in the Constitution, he added, “So help me God”, and kissed the Bible, thereby establishing his own first presidential tradition.

“It is done,” Livingston said, and, turning to the crowd, cried out, “Long live George Washington, President of the United States.”

George Washington said:

Men may speculate as they will, they may talk of patriotism; they may draw a few examples from current story – but whoever builds upon it as a sufficient basis for conducting a long and bloody war will find themselves deceived in the end – For a long time it may of itself push men to action, to bear much, to encounter difficulties, but it will not endure unassisted by Interest.

On August 17, 1790, George Washington visited Newport Rhode Island – and visited the Jewish congregation of the Touro Synagogue (which still stands – gorgeous building. We went on a field trip there in grade school). The congregation presented an address to George Washington, welcoming him to Newport, and to their synagogue. A couple of days later George Washington wrote an eloquent response. Both the address as well as Washington’s response were printed in all of the “national” newspapers at the time.

August 21st, 1790

To the Hebrew Congregation in Newport Rhode Island.

Gentleman.

While I receive, with much satisfaction, your Address replete with expressions of affection and esteem; I rejoice in the opportunity of assuring you, that I shall always retain a grateful remembrance of the cordial welcome I experienced in my visit to Newport, from all classes of Citizens.

The reflection on the days of difficulty and danger which are past is rendered the more sweet, from a consciousness that they are succeeded by days of uncommon prosperity and security. If we have wisdom to make the best use of the advantages with which we are now favored, we cannot fail, under the just administration of a good Government, to become a great and happy people.

The Citizens of the United States of America have a right to applaud themselves for having given to mankind examples of an enlarged and liberal policy: a policy worthy of imitation.

All possess alike liberty of conscience and immunities of citizenship. It is now no more that toleration is spoken of, as if it was by the indulgence of one class of people, that another enjoyed the exercise of their inherent natural rights. For happily the Government of the United States, which gives to bigotry no sanction, to persecution no assistance, requires only that they who live under its protection should demean themselves as good citizens, in giving it on all occasions their effectual support.

It would be inconsistent with the frankness of my character not to avow that I am pleased with your favorable opinion of my Administration, and fervent wishes for my felicity. May the children of the Stock of Abraham, who dwell in this land, continue to merit and enjoy the good will of the other Inhabitants; while every one shall sit in safety under his own vine and figtree, and there shall be none to make him afraid. May the father of all mercies scatter light and not darkness in our paths, and make us all in our several vocations useful here, and in his own due time and way everlastingly happy.

G. Washington

From Joseph Ellis’ book The Founding Brothers:

First, it is crucial to recognize that Washington’s extraordinary reputation rested less on his prudent exercise of power than on his dramatic flair at surrendering it. He was, in fact, a veritable virtuoso of exits. Almost everyone regarded his retirement of 1796 as a repeat performance of his resignation as commander of the Continental Army in 1783. Back then, faced with a restive and unpaid remnant of the victorious army quartered in Newburgh, New York, he had suddenly appeared at a meeting of officers who were contemplating insurrection; the murky plot involved marching on the Congress and then seizing a tract of land for themselves in the West, all presumably with Washington as their leader.

He summarily rejected their offer to become the American Caesar and denounced the entire scheme as treason to the cause for which they had fought. Then, in a melodramatic gesture that immediately became famous, he pulled a pair of glasses out of his pocket: “Gentlemen, you will permit me to put on my spectacles,” he declared rhetorically, “for I have not only grown gray but almost blind in service to my country.” Upon learning that Washington intended to reject the mantle of emperor, no less an authority than George III allegedly observed, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.” True to his word, on December 22, 1783, Washington surrendered his commission to the Congress, then meeting in Annapolis: “Having now finished the work assigned me,” he announced, “I now retire from the great theatre of action.” In so doing, he became the supreme example of the leader who could be trusted with power because he was so ready to give it up.

George Washington’s last words:

“I feel myself going. I thank you for your attentions; but I pray you to take no more trouble about me. Let me go off quietly. I cannot last long.”

Mark Twain wrote in 1871:

I have a higher and greater standard of principle [than George Washington]. Washington could not lie. I can lie but I won’t.

Gouverneur Morris said, upon the death of this great man:

It is a question, previous to the first meeting, what course shall be pursued. Men of decided temper, who, devoted to the public, overlooked prudential considerations, thought a form of government should be framed entirely new. But cautious men, with whom popularity was an object, deemed it fit to consult and comply with the wishes of the people. AMERICANS! — let the opinion then delivered by the greatest and best of men, be ever present to your remembrance. He was collected within himself. His countenance had more than usual solemnity — His eye was fixed, and seemed to look into futurity. ‘It is (said he)too probable that no plan we propose will be adopted. Perhaps another dreadful conflict is to be sustained. If to please the people, we offer what we ourselves disapprove, how can we afterwards defend our work? Let us raise a standard to which the wise and the honest can repair. The event is in the hand of God.’–this was the patriot voice of WASHINGTON; and this the constant tenor of his conduct.

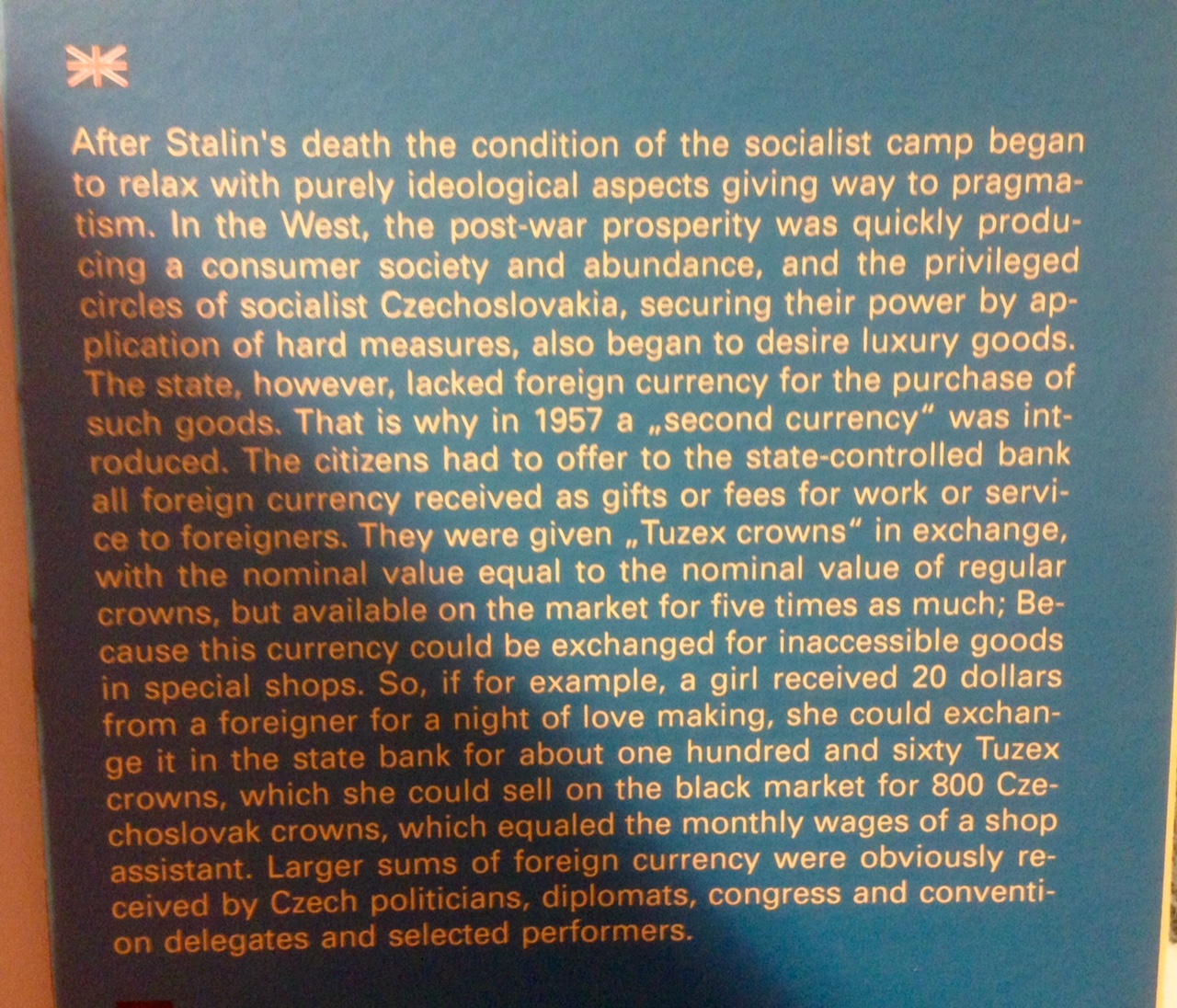

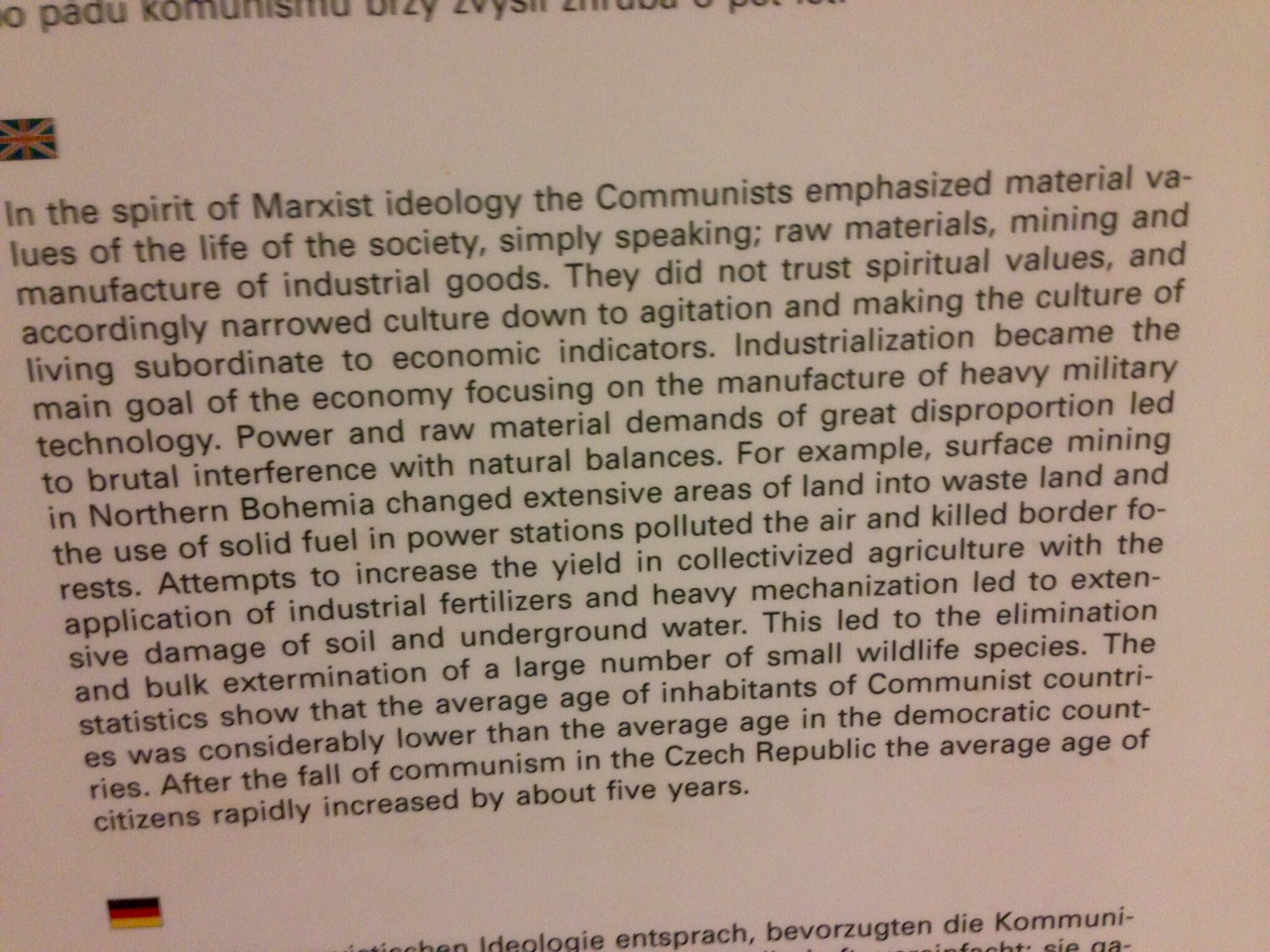

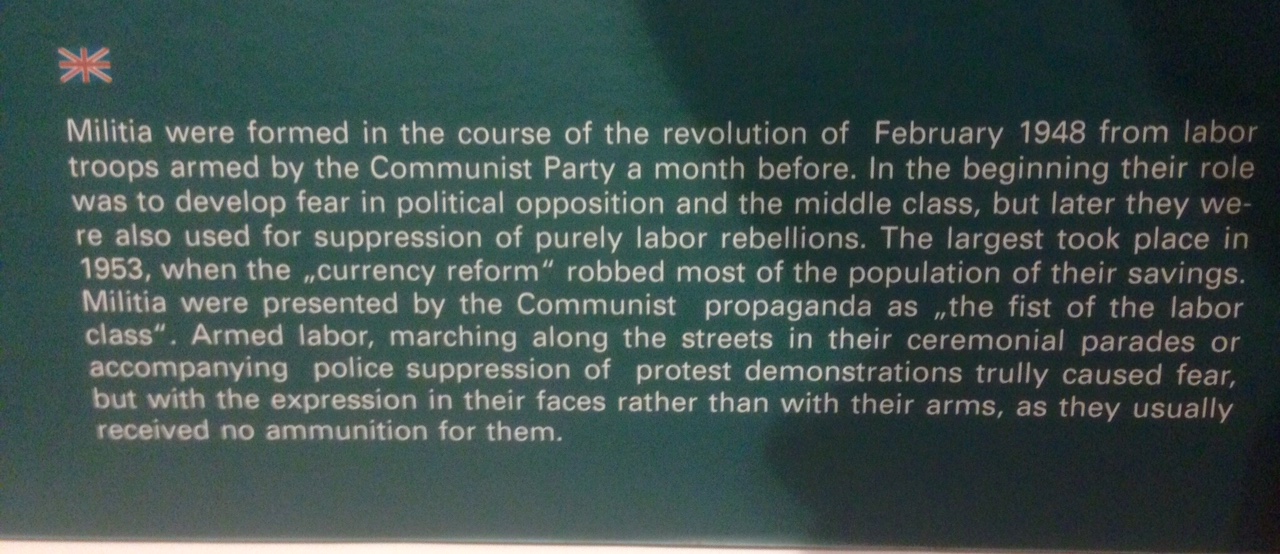

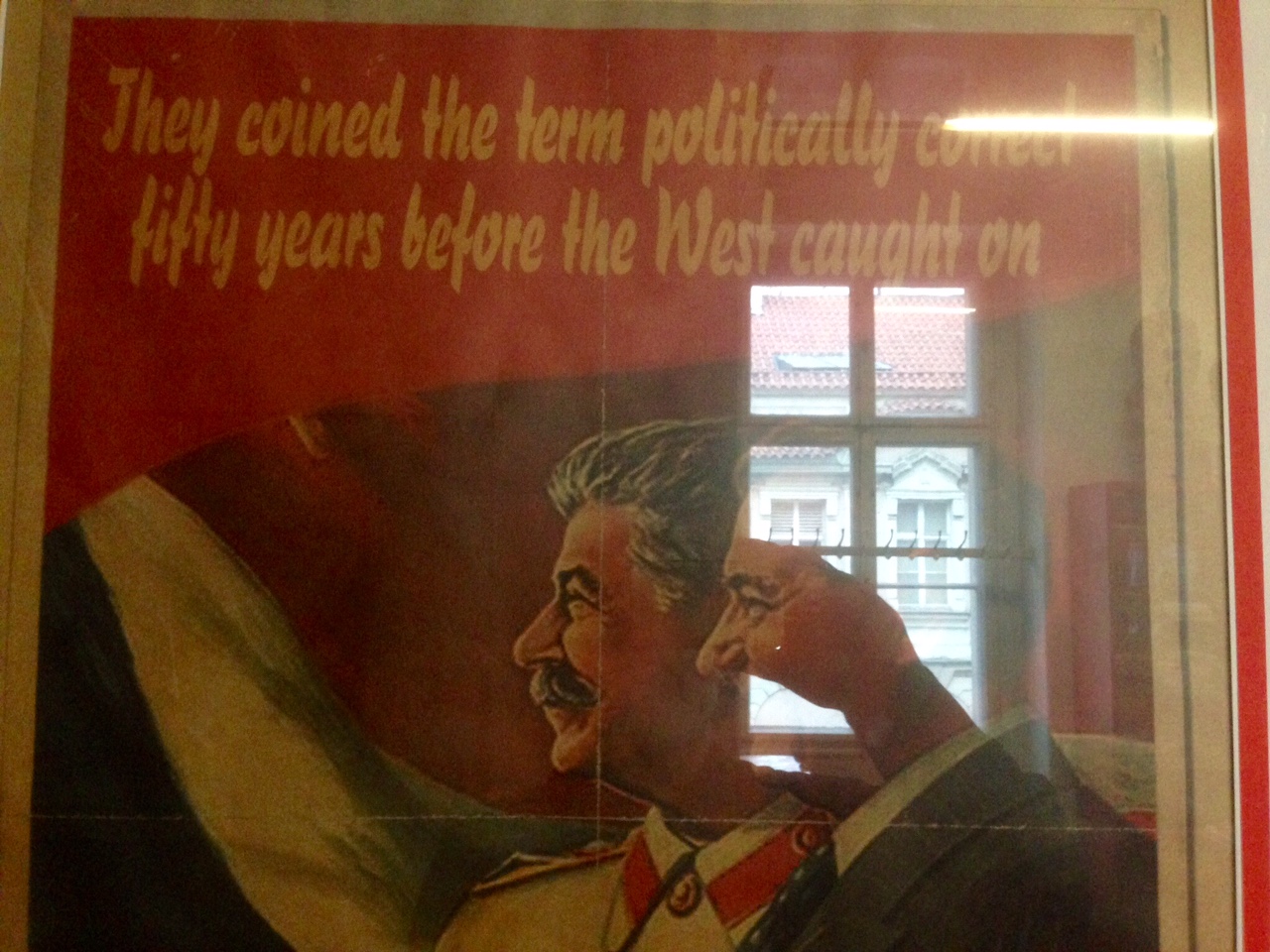

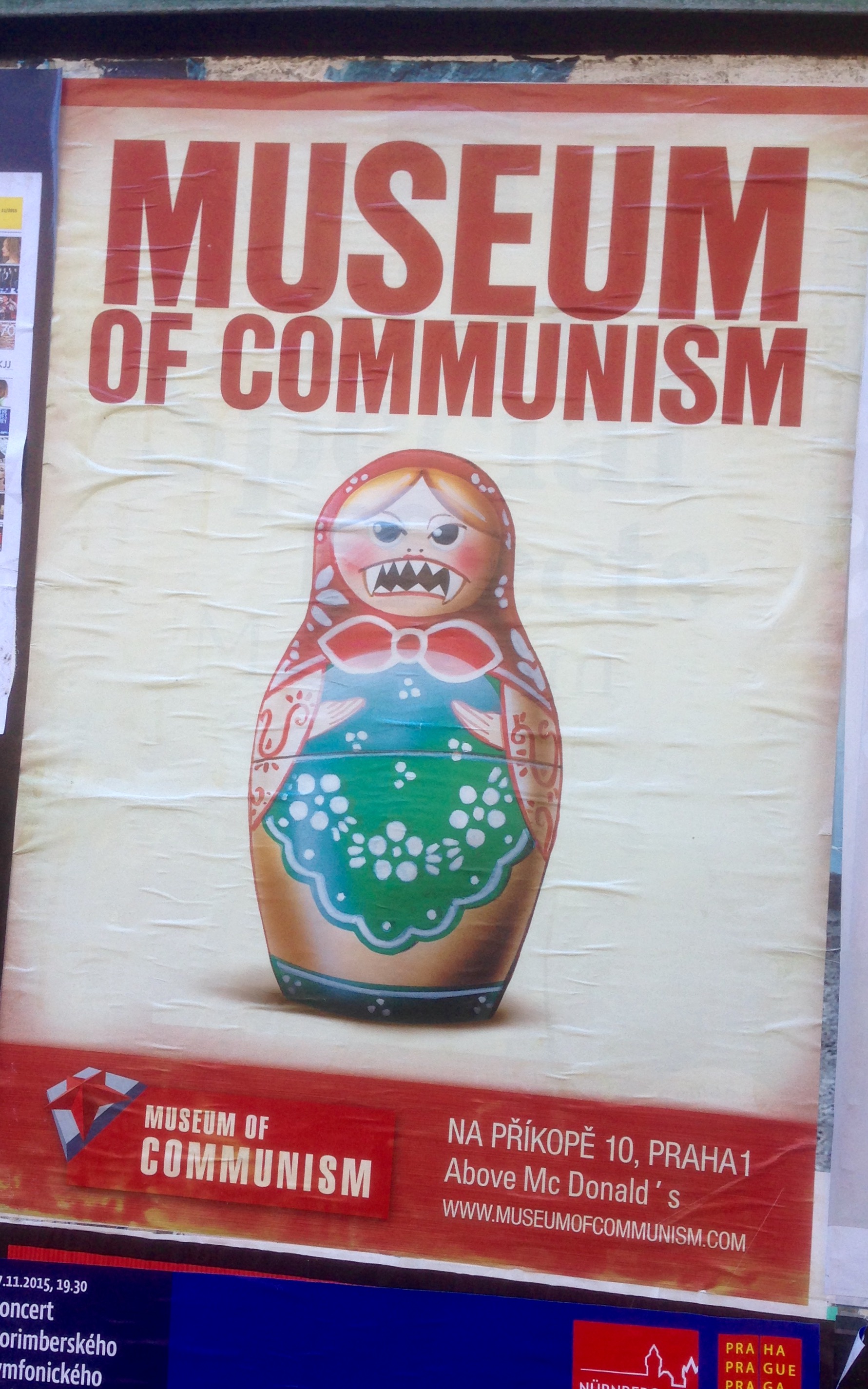

I saw this museum advertised the first day we were in Prague and made a note to see it while we were here. I loved the poster, for one thing. It came down to our last weekend and I realized we still needed to go, so we set out. I have to say it is one of the most affecting places I’ve visited over here.

I saw this museum advertised the first day we were in Prague and made a note to see it while we were here. I loved the poster, for one thing. It came down to our last weekend and I realized we still needed to go, so we set out. I have to say it is one of the most affecting places I’ve visited over here.