by the Night Writer

After grazing our way around the Budejovice square it was time for Graz, Austria (pronounced “Grahts”). We turned south and headed into the Alps on our way to the capital city of Styria. Graz is only a few hundred meters above sea level, but you have to go up, over and through some mountains before you can get there. Gratz is in a basin, protected by the mountains, so it’s weather is influenced more by the Mediterranean than the colder and windier capital, Vienna. It’s much more temperate, which is good news for the college students: the city is home to six universities, in case you’re interested in studying abroad.

The warm weather followed us, so we didn’t have to contend with any snow as we navigated the mountains. We did go through some pretty long tunnels, though, which really messed with our GPS. It would lose the signal and give us instructions such as “turn left in 100 meters” – which really wouldn’t have been a very healthy thing to do since the end of the tunnel was still a couple of kilometers ahead. No doubt the tunnels made for a faster and safer trip than driving over the mountains, but they do tend to limit your view, which is too bad since we saw some pretty dramatic things when there were only clouds over our heads.

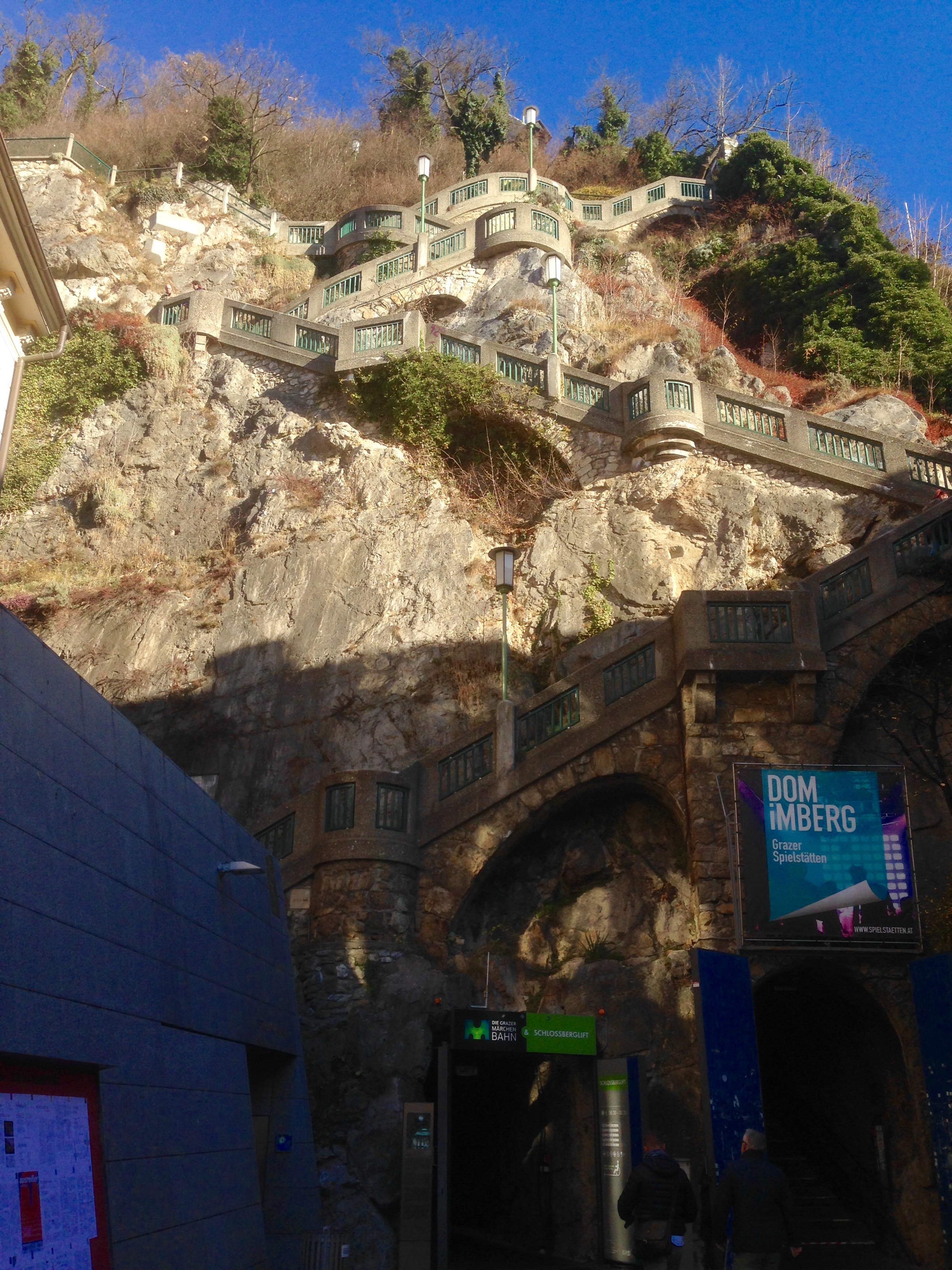

Graz is a relatively simple place to get around in. Essentially all public transit options run through the train station (the Haptbahnhof) and city center (Hauptplatz). The main square is very compact compared to Prague Old Town Square or the Budejovice square, but was jammed with vendors and Christmas Markets. Overlooking the square is the Schloßberg, a rocky hill that commands the area. We were told that the Schloßberg is very worth seeing, and my vestigial German vocabulary told me that “Schloß” means “Castle” so we spent some time looking for a castle. It turns out the castle no longer exists. It was such an impregnable fortress that even Napoleon couldn’t defeat it. Napoleon did manage to defeat the Austrians, though, without taking the castle – but demanded that the Austrians destroy the castle as part of the surrender terms (Treaty of Schönbrunn). The town itself paid a ransom to Napoleon to preserve the clock tower (the symbol of the town) and the bell tower. The grounds were later turned into a public park and it is a magnificent location for concerts and events, with a great view of the city.

There are a few ways to get up to the Schloßberg; you can buy a ticket on the funicular, or a ticket to use the lift, or you can climb the 390 stairs on the side of the rock. (None of these options were available to Napoleon).

I did not choose the stairs. The Reverend Mother and Tiger Lilly did, however. Here they paused at around 313 steps.

When you get to the top you get a great view of the city (if it isn’t foggy), plus the clock tower that is the city’s trademark.

Here’s another perspective of the Schloßberg, this time from the Hauptplatz, looking up to the red roofs on the shoulder of the rock above.

I tried on another hat; this one a beaver top hat. Not quite my look, but Tiger Lilly probably would have rocked it. She wanted nothing to do with it, though.

If Frank Gehry were to design an island, this is what it would look like. It actually is a boat and night club moored in the Mur, but everyone calls it “the Island”.

The Eggenbergs and Schloß Eggenberg

Every region has had its dynastic families, particularly from the Manorialism era. Families such as the Habsburgs in Germany, Austria, Bohemia and Spain (more on them in a later post), or the Savoys and Medicis in Italy. In Austria, and especially Styria, the dynastic family was the Eggenbergs, who were aligned with the Habsburgs. Balthasar Eggenberger, an astute business man and financier, as well as an exceptionally canny politician, was the royal mint-master for Emperor Frederick III (yes, a Habsburg), which essentially gave him a license to print (or stamp) money. He first established the family estate near Graz in the mid-1400s, and this later was expanded and greatly modified into the classic Baroque palace, Schloß Eggenberg in the 17th century by Hans Ulrich von Eggenberg – an even more astute politician than his great-grandfather. Hans Ulrich was raised Protestant but converted to Catholicism in order to serve his lord, Arch-duke Ferdinand (another Habsburg) who later became Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor, with Hans Ulrich serving as, in effect, his Prime Minister. They persecuted the Catholic Reformation in Bohemia (a reform movement within the church, but not Protestant) – and matched wits with the royal Bourbons in France and their Cardinal Richelieu. (Richelieu, while Catholic, was virulently anti-Habsburg, and the French Catholics actually supported the German Protestants in Bohemia.) Richelieu and Hans Ulrich were likely the two most powerful non-royal men in Europe in the 17th century.

I don’t know if that information whets your historical interest or smothers it, but it serves as a backdrop to the beautiful Schloß Eggenberg. While the Palace is closed in the winter months (there is no electricity or heat, deliberately, so as to preserve the extensive ceiling paintings throughout the second floor), you can walk the grounds and even enter the inner courtyard. For all of its illustriousness and focus on the eternal, the dynasty was ultimately very mortal. The last male heir of the line died in 1717 of appendicitis at the age of 13.

While the wealth and power of the family greatly diminished, the ancestral home is still magnificent. We strolled and enjoyed the gardens (except for the Cat Pee bushes) and the wandering peacocks that are the sole residents these days. I also sat on a bench in front of the palace and tried to imagine the fine coaches that had once pulled up here, or the couriers on lathered horses bringing urgent missives in the dead of night. I would love to come back here in the summertime and tour the interior as well as the other structures. The link above does give you a good idea of what we missed out on this trip.

The palace grounds are open in the winter for a nominal 4 Euros per person, helping to give you a sense of the scale and power that was once projected here.

The palace is still in its 17th century state – no electricity or heat – but this is what has preserved the 17th century paintings.

The ever popular “Cat Pee” bush. I named it that because that is what it smells like. As to the “ever popular” part, it’s certainly not to my taste but the rich folks in Europe must have liked it because we’ve encountered here, at Castello Miramare and other places. And believe me, you’ll know when you’ve encountered it.