by the Night Writer

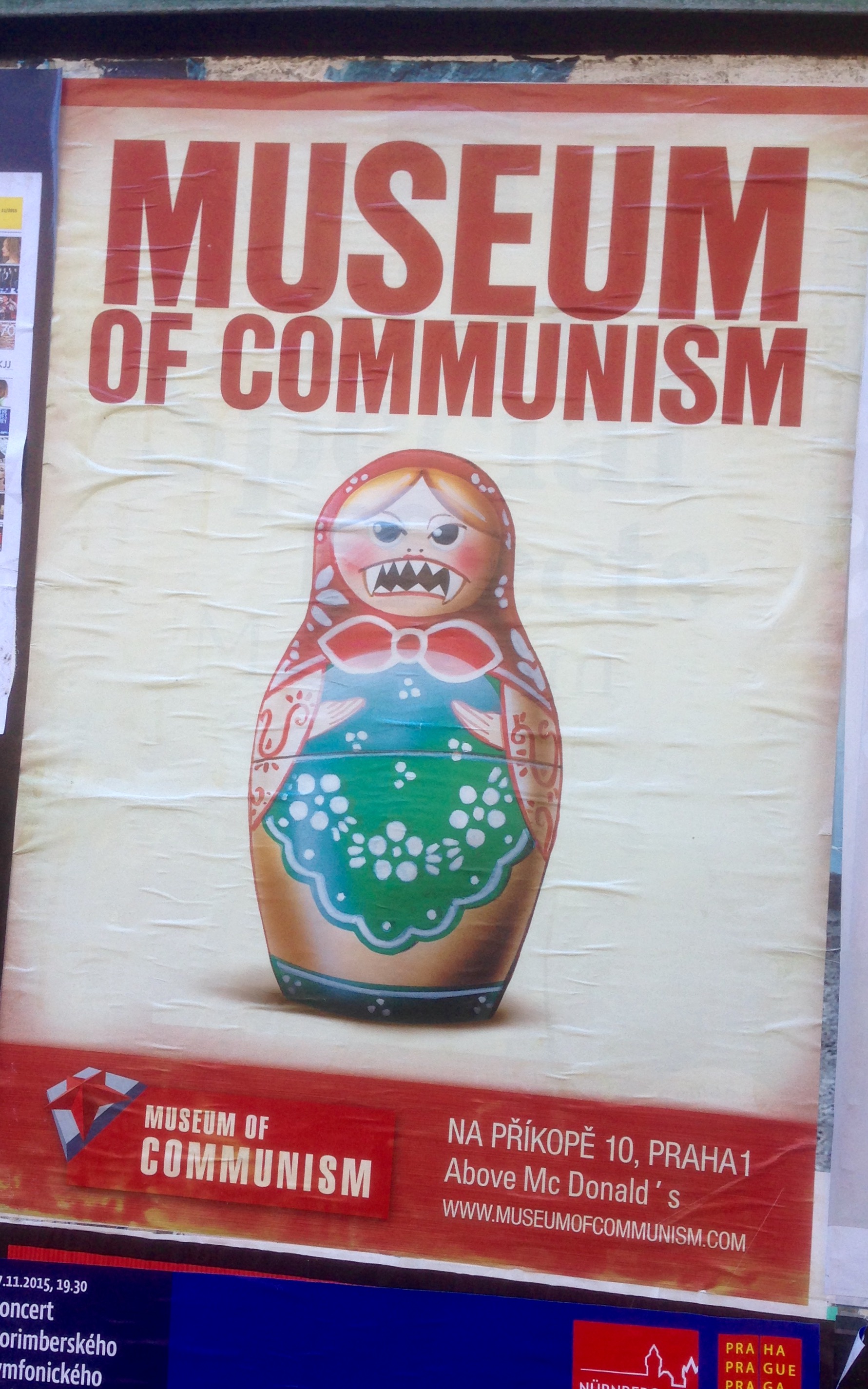

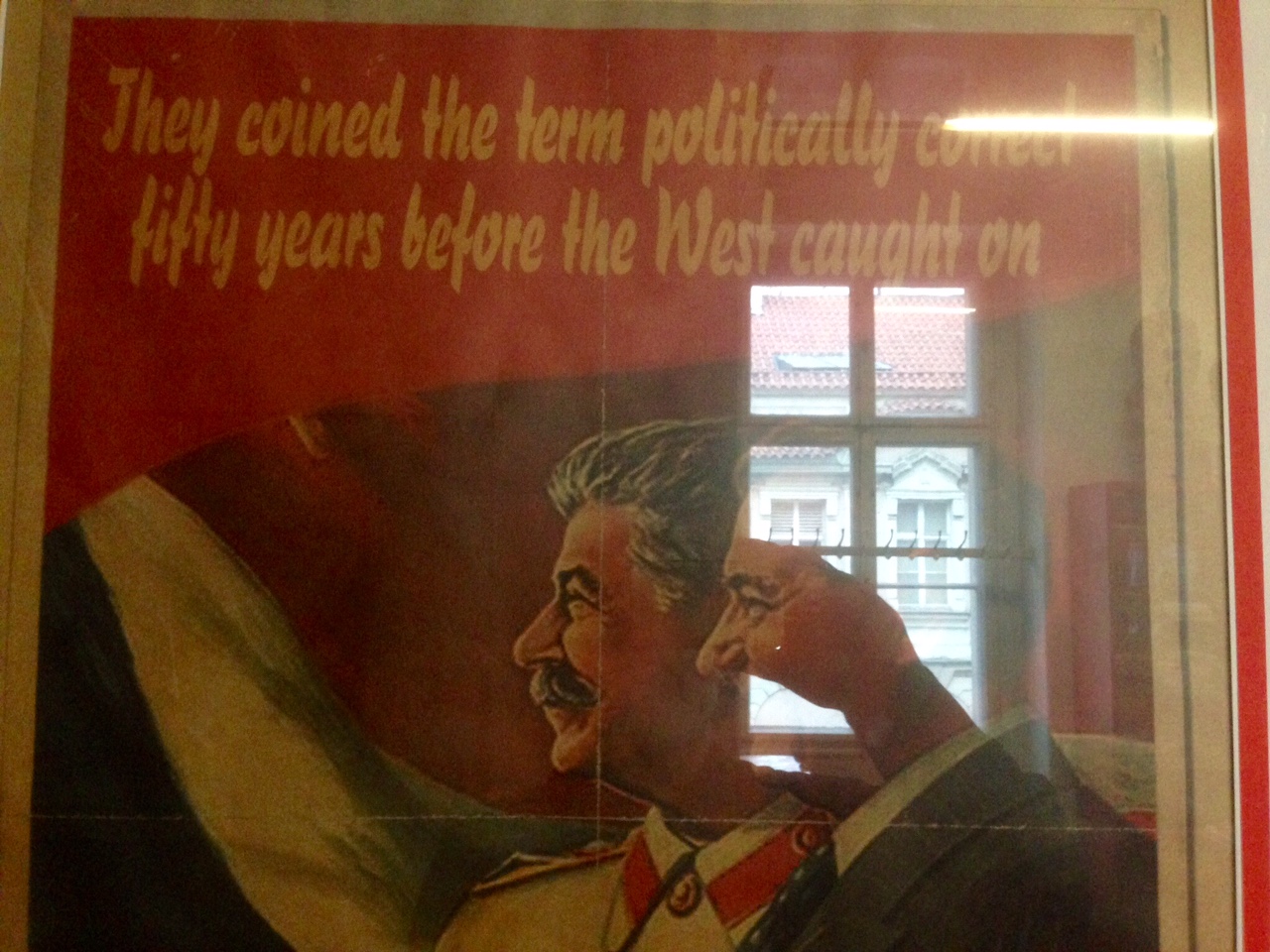

I saw this museum advertised the first day we were in Prague and made a note to see it while we were here. I loved the poster, for one thing. It came down to our last weekend and I realized we still needed to go, so we set out. I have to say it is one of the most affecting places I’ve visited over here.

I saw this museum advertised the first day we were in Prague and made a note to see it while we were here. I loved the poster, for one thing. It came down to our last weekend and I realized we still needed to go, so we set out. I have to say it is one of the most affecting places I’ve visited over here.

The Czechs are not known for their sense of humor, but it can be found, such as their placing this museum in the same building as a McDonald’s, next to a casino, and across the street from Benetton. There are also some rather rude jokes at the expense of the Russians and Communism in the gift shop, but the museum itself is serious. One might even say, “deadly serious.”

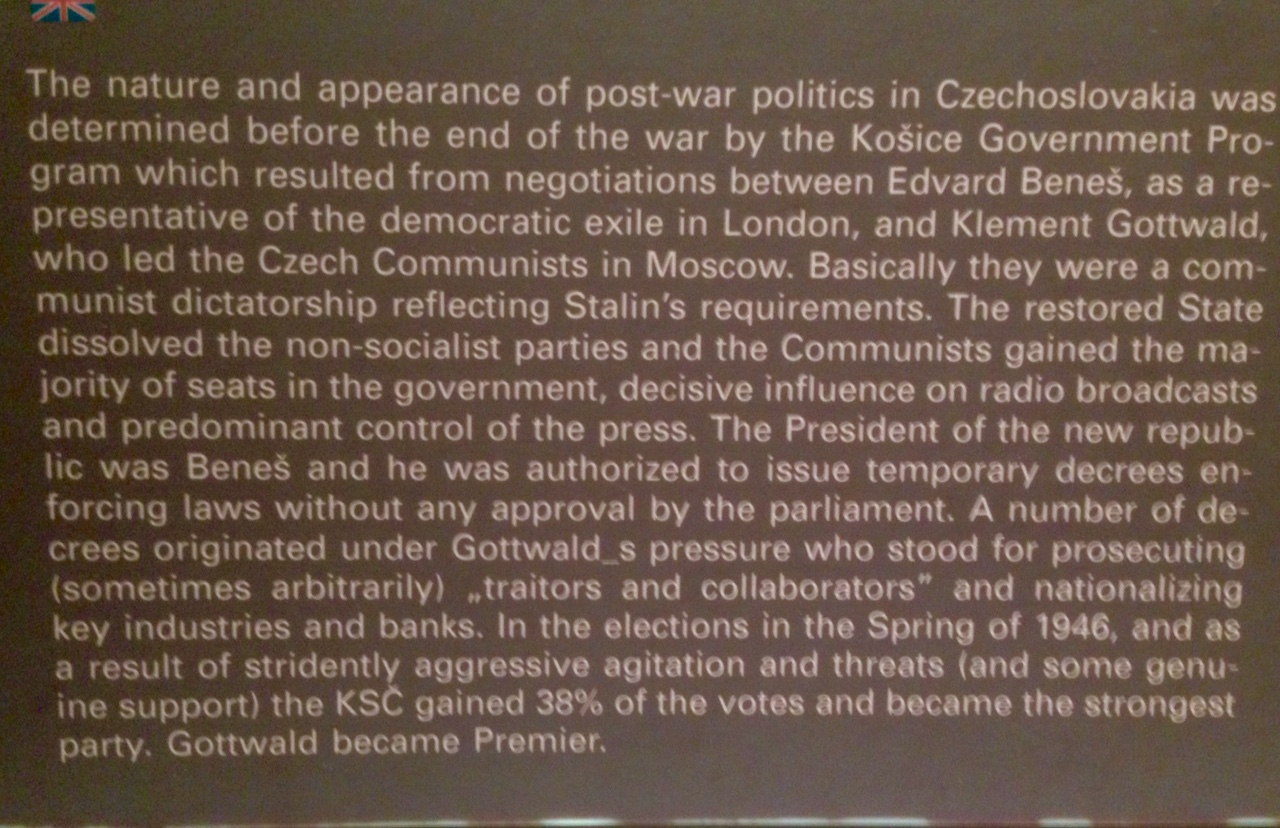

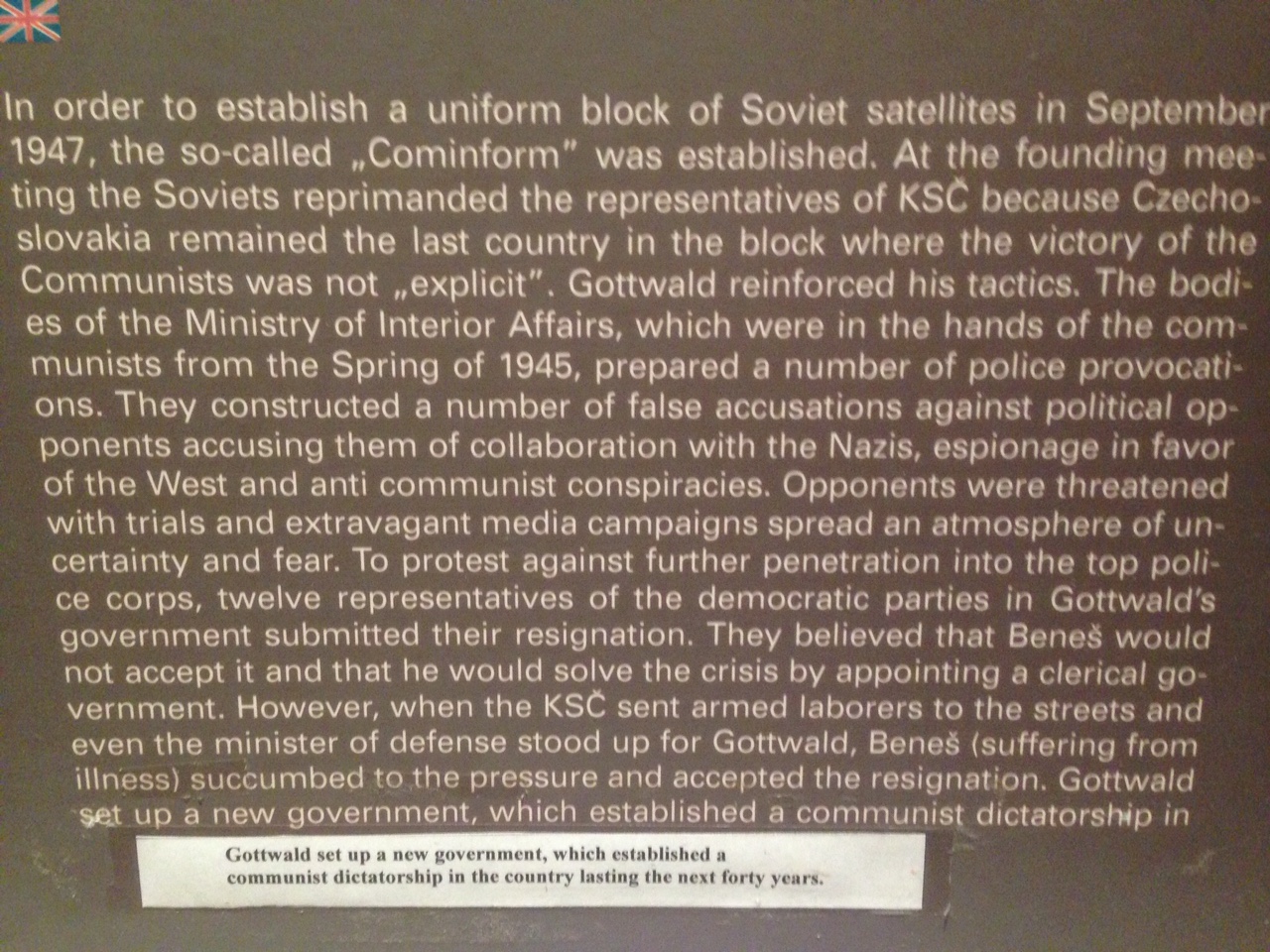

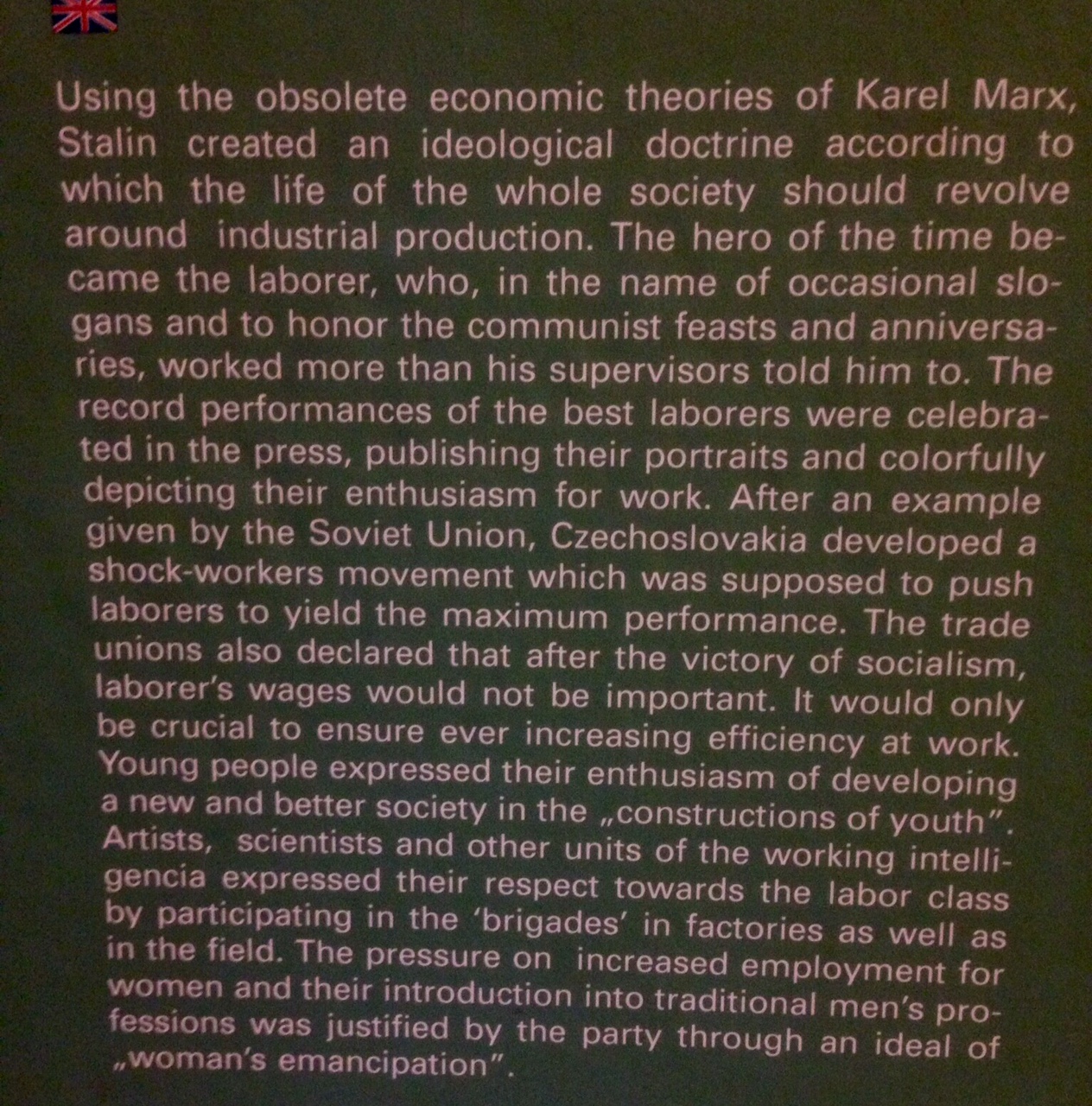

I could write in greater detail about my impressions, but perhaps it’s better to let the people who lived through it do it in their way. I took photos of some of the English-language placards that accompanied the photos and displays. These are also available in French, German, Czech, and several other languages for greater edification. Let’s let them tell the story.

“…authorized to issue temporary decrees enforcing laws without any approval of the parliament…” hmmm?

Targeting opponents with heinous accusations and show trials, and extravagant media campaigns.

A “shock-workers” movement to push laborers to maximum effort, and trade unions declaring that “after the victory of socialism, laborer’s wages would not be important.”

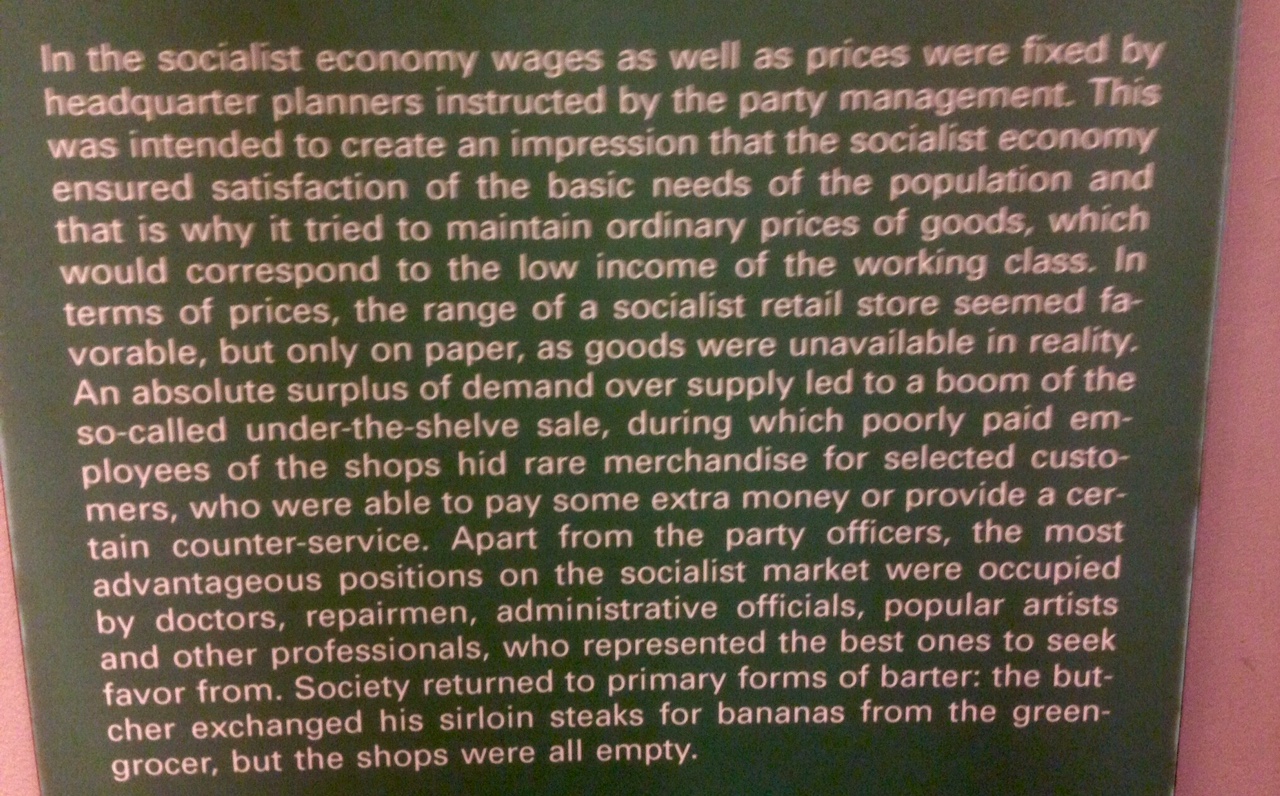

Supply and Demand? Why, there ought to be a law…

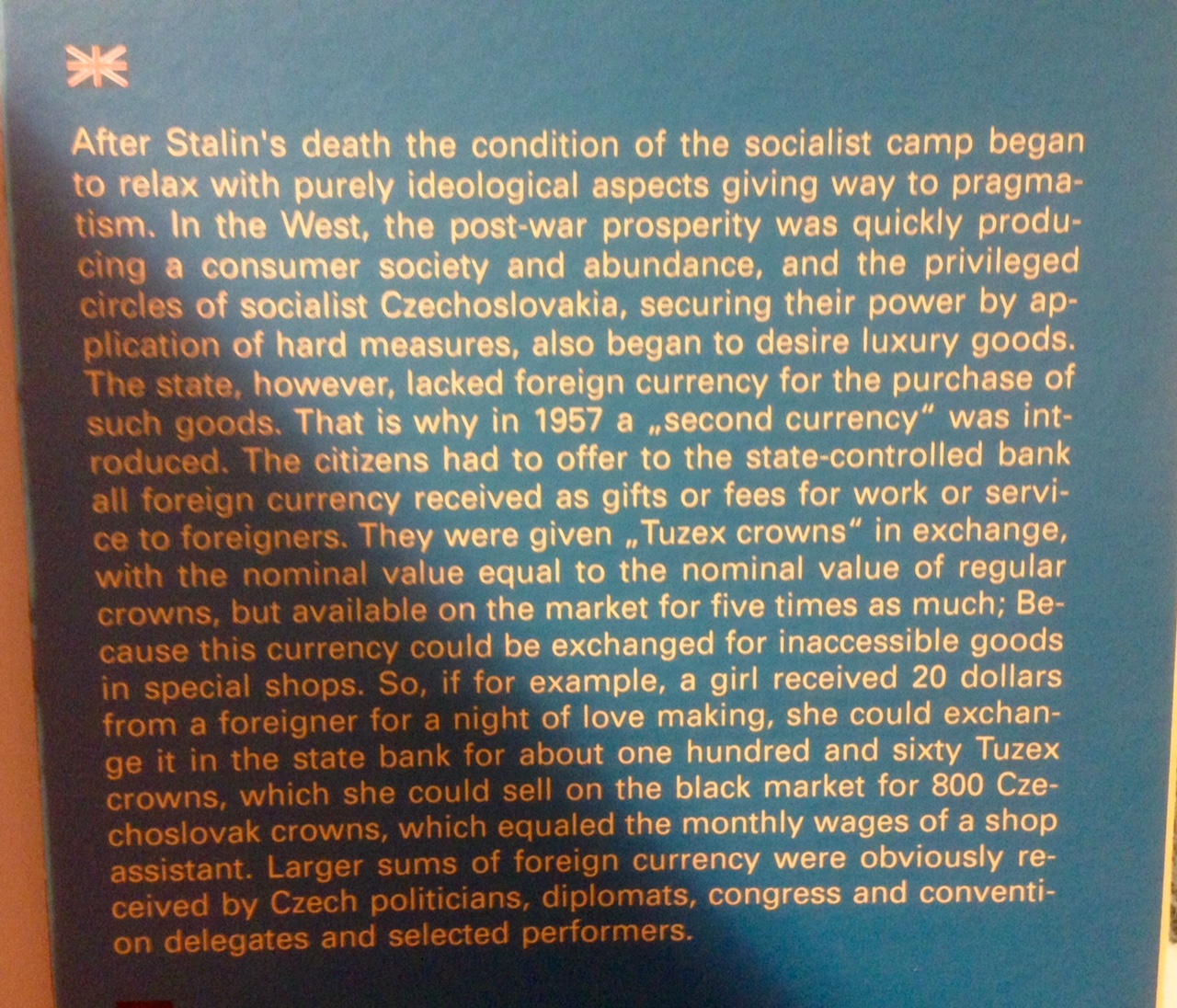

Those in power always find a way to get their luxury goods. Or their groceries.

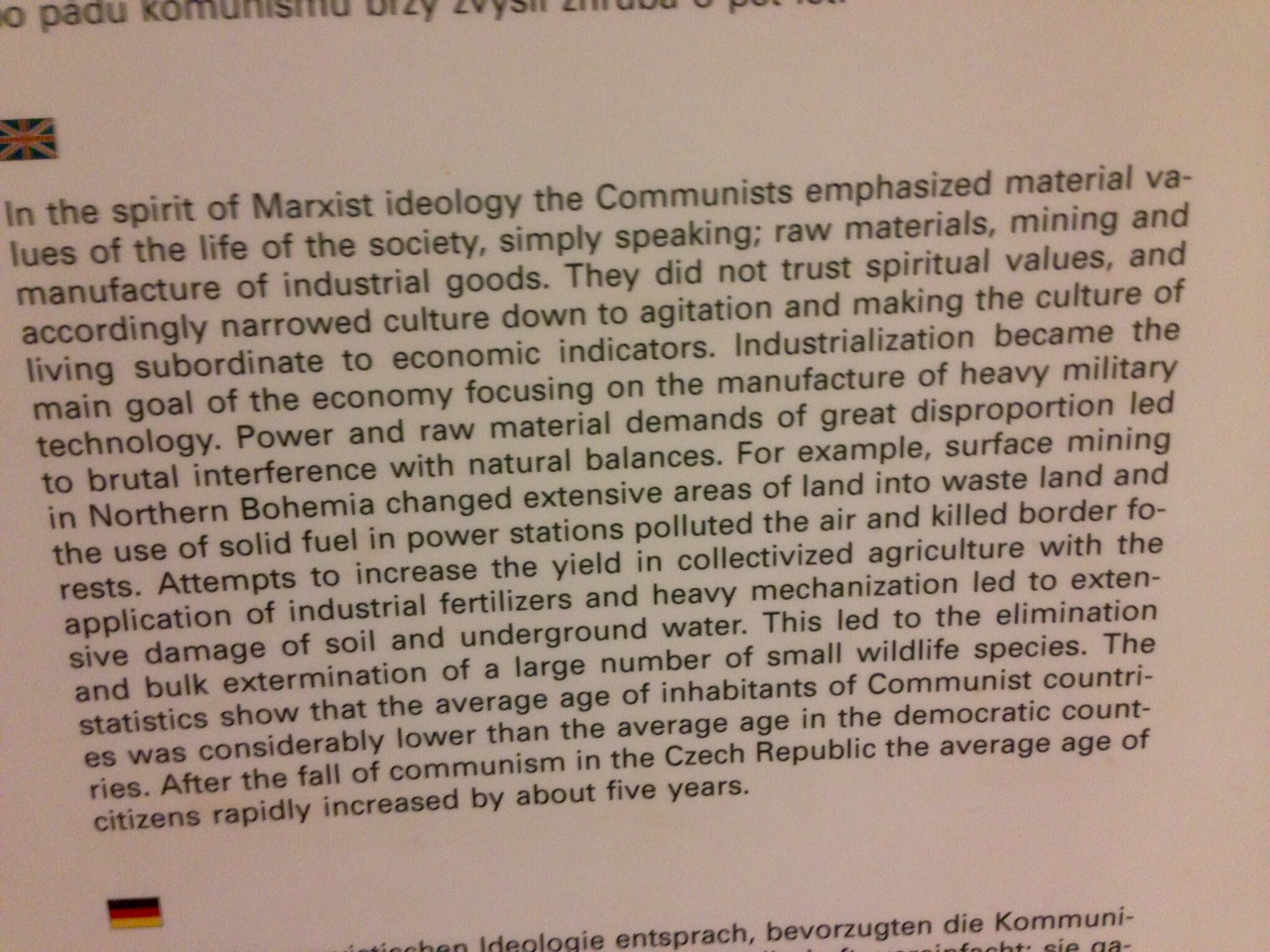

There are no spiritual values, outside the State. There is no beauty, but what serves the State. There is no eternity…but the State. Rape, pillage and pollute the land and consequently the people; it doesn’t matter as long as the State benefits.

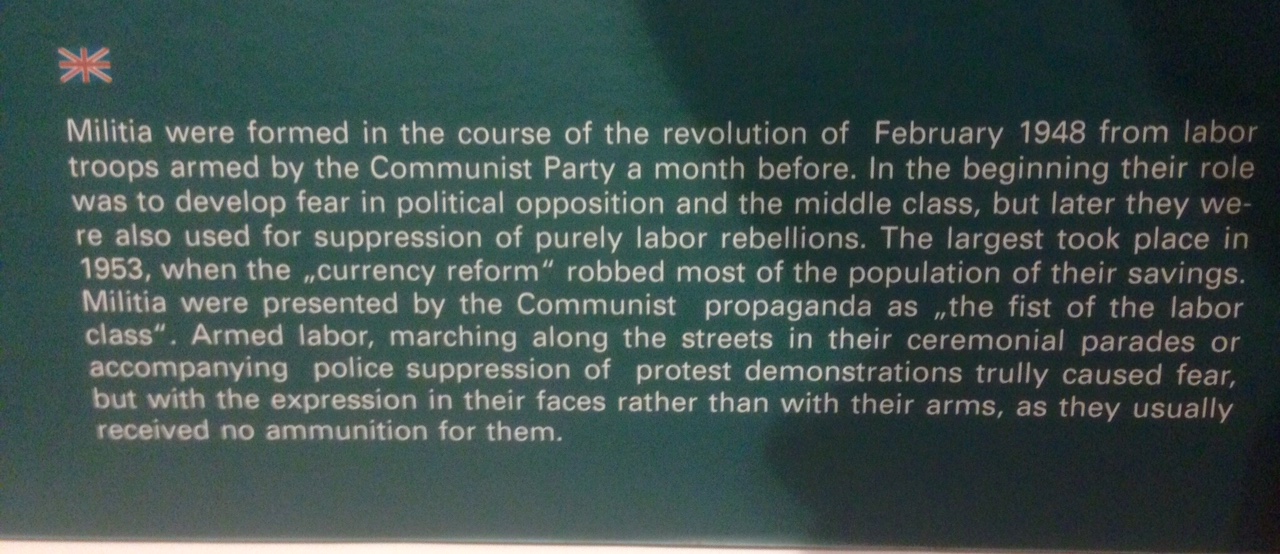

A well-regulated militia?

You can’t find a more “well-regulated” militia than that: armed groups established by the government as “the fist of the labor class” to intimidate its enemies, especially the labor class. Of course, they couldn’t be trusted with bullets for their guns.

To get a better feel for the exhibits, take the virtual tour here.

You wind your way through the rooms of the museum in what was once the Savarin Palace. The exhibits feature authentic memorabilia, though “memorabilia” is such a trifling-sounding word that implies nostalgia, and the memories here are far from fond. The last portion on your way out (before the gift shop, Comrade Lenin) is devoted to a small viewing room that plays a short film in a loop describing Czech life from the Communist takeover to the Velvet Revolution in 1989. It was called the “Velvet” Revolution because shots weren’t fired, but that does not mean it was peaceful or that the history leading up to it wasn’t bloody.

I can remember, as a kid, watching the news in 1969 as the Soviet tanks rolled into Prague to crush the “Prague Spring” and any nascent hopes of reform within the Czech Communist Party. This, too, was depicted in the film and on the wall outside the viewing room: riots, beatings, tear-gassing, armed troops and war-machines rolling over the cobblestones of Wenceslas Square that we’d come to know so well, plain-clothes agents in the crowd tackling and kicking protesters, plus accounts of three students who self-immolated in protest against Communist control.Despite the incessant cradle-to-grave indoctrination, propagandizing, intimidation and spying, the Communists couldn’t stamp out hope and a desire for freedom from such a dehumanizing existence.

Communist doctrine often referred to the “inevitability of history” and Communism’s ultimate victory, yet by the 1980s, history was clearly turning against Communism as Poland, Hungary and East Germany shook off the shackles of totalitarianism. Even so, Czechoslovakia’s escape was not a done deal. The first protest drew maybe 10,000 to Wenceslas; as the week went on the numbers grew, until finally 500,000 were crowding in every night to apply pressure and turn the tables of intimidation as they watched their one-time rulers caving in. (Velvet Revolution timeline and summary here). Blood was still being spilled; certain claws do not release easily, after all. The film ends with a bittersweet poem and images describing how much sweeter survival is after all the bitter pain that preceded it.

As I said, it is very affecting. As we left, I stopped at the desk of the woman who had sold us our tickets. She was about my age, and would have seen 1969 and 1989, and spoke very good English. She was standing, and turned to me. “Thank you,” I said, and she responded with a small, polite smile. “And thank you to people of Prague,” I added, and received a slow, solemn nod.