I’ve always been on the lookout for films with strong messages dealing with honor and character in this series for teen-age boys, and the stories can be fictional, factual or a bit of both. It’s a bonus, however, when we have a chance to see something of a historical nature that can also help us learn something about the world today. Last month our movie was The Wind and the Lion, a mostly historical story with some movie-making embellishments that provided a useful sketch of early 20th century geo-politics while still offering a rip-roaring adventure.

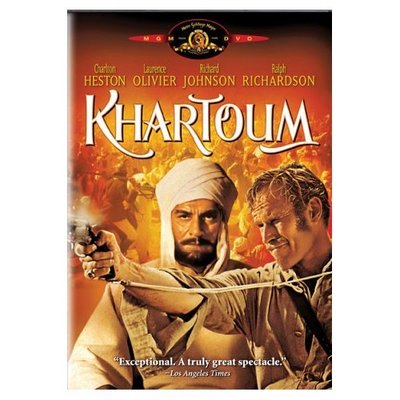

Afterwards the young men seemed to be interested in the Middle Eastern dynamics of that time and how these were still resonating today. Our next class is Thursday night and I’ve decided to follow up on that with a film I happened to catch on AMC right after Charlton Heston died: Khartoum. It’s an amazing and reliably accurate telling of Islamic jihad in the late 1800s that has striking, and sobering, parallels to today.

Afterwards the young men seemed to be interested in the Middle Eastern dynamics of that time and how these were still resonating today. Our next class is Thursday night and I’ve decided to follow up on that with a film I happened to catch on AMC right after Charlton Heston died: Khartoum. It’s an amazing and reliably accurate telling of Islamic jihad in the late 1800s that has striking, and sobering, parallels to today.

Here’s the set-up for the story: It’s the 1880s and most countries in the Middle East are under the influence, if not outright control, of one or another of the European nations. Egypt, supported by England, controls the Sudan, including the capital city of Khartoum. A few years earlier a British officer, Charles George “Chinese” Gordon, had been Governor-General of the Sudan and largely stamped out the slave trade in the country. As this had been the major industry in the land, the economy had subsequently tanked and in the hard times a religious leader, Muhammad Ahmad, proclaimed himself the Mahdi (Expected One) and rallied thousands to holy war to drive out the Egyptians and Europeans. He has early successes and England sends 10,000 men under General Hicks to put down the insurgency (Gordon had been recalled to England a few years earlier), but the Mahdi lures them into the dessert and then wipes out the entire command. This disaster is not well-received back in England where the government of Prime Minister William Gladstone is on shaky ground and the public is outraged at the loss of the expedition but also weary of foreign entanglements, especially on behalf of their Egyptian allies. While England and Gladstone want little to do with the Sudan, they need the Egyptians and especially the Suez Canal.

As portrayed in the movie, Gladstone (Ralph Richardson) wants to wash his hands of the Sudan but is experiencing pressure to rescue the Egyptian and European citizens in the city before it is overwhelmed by the Mahdi’s (Laurence Olivier) army. There is no way he wants to commit an army to that cause, however, so he charts a canny course of sending the hero Gordon (Heston) back, alone, to Khartoum to organize an evacuation. Gordon, a national hero with a string of successes in China as well as Africa, is known to be a difficult person to control because of his deep Christian faith and what some described as arrogance and mysticism. He nevertheless accepts the apparently hopeless mission, knowing that he’s being sent as a political gesture but also having an agenda of his own. It turns out he grew to love the Sudan and its people during his earlier duty and he couldn’t abide the thought of abandoning his city, or of England abandoning its allies, to the foreseen slaughter of the Mahdi.

Upon arriving in Khartoum he does evacuate some of the Europeans, but also sets about rallying the Egyptian troops and the citizenry to defend the city, while playing a brilliant but dangerous game of military, administrative and political chicken, simultaneously keeping the Mahdi at bay while hoping to hold out long enough for Gladstone to change his mind and send relief. While the movie sets up the primary conflict between Gordon and the Mahdi, it really is a 3-way battle with Gladstone showing his own determination and tactical abilities. The Mahdi, despite his own mysticism, recognizes the danger of turning Gordon into a martyr, as does Gladstone but for different reasons. Gordon knows that this is where he has them both. One of the great lines in the movie is when Gordon says, “Every man has a final weapon: his own life. If he’s afraid to lose it, he throws the weapon away.”

Both the Mahdi and Gladstone, again for their own reasons, try different ways to induce Gordon to leave. By this time, English public opinion is pressuring Gladstone to send a relief column to Gordon’s rescue. Ultimately Gladstone makes a big show of doing just that, marching a regiment through London to take ship for Africa, ostensibly to support Gordon but secretly ordered to move slowly in the hopes that Gordon will ultimately “see reason” and abandon his quest. I won’t offer a spoiler here on how it comes out (go to your history books if you want that), but the ensuing battle of wills between the three men, plus lots of real battles between armies, makes this a tense and gripping story with some interesting perspectives on the nature of power, the power of belief, and the designs of destiny.

The history is pretty solid in this story and the movie hews pretty closely to what is recorded. There are a lot of resources for historians to refer to, including the newspapers of the time, Gordon’s own writings during the 10-months of the siege, and the writings of Colonel Sir Rudolph Slatin, a contemporary and friend of Gordon’s who got to spend several years as the “guest” of the Mahdi himself.

Great Quotes:

William Gladstone: “I don’t trust any man who consults God before he consults me.”

Gen. Charles Gordon: “Every man has a final weapon: his own life. If he’s afraid to lose it he throws the weapon away.”

Gordon: “I’m known to be a religious man, yet I’m a member of no church. I’ve been introduced to hundreds of women, yet I’ve never married. I daresay that no one’s ever been able to talk me into anything.”

Gordon: “While I may die of your miracle, you will surely die of mine.”

About Fundamentals in Film: this series began as a class I taught to junior high and high school boys as a way to use the entertainment media to explore concepts of honor, honesty, duty and accountability. The movies were selected to demonstrate these themes and as a contrast to television that typically either portrays men as Homer Simpsons or professional wrestlers, with little in between those extremes. I wrote questions and points to ponder for each movie to stimulate discussion and to get the boys to articulate their thoughts and reactions to each movie. I offer this series here on this blog for the benefit of parents or others looking for a fun but challenging way to reinforce these concepts in their own families or groups. I’m also always open to suggestions for other movies that can be added to the series. You can browse the entire series by clicking on the “Fundamentals in Film” category in the right sidebar of this blog.

Los casinos son lugares en los que las personas pueden dsfrutar de una variedad de juegos de

azar. Algunos de los juegos más comunes se encuentran las

máquinas tragamonedas, la ruleta, el póker y ell blackjack.

Muchos jugadores loss visitan en busca de diversión, mientras que otros lo hacen esperando ganar dinero.

Actualmente, los casinos enn línea también han ganado mycha atención,

permitiendo a los usuarios jugar desde laa comodidad de su hogar.

Estops ofrecen bonificaciones atractivas y una experiencia

interactiva.

Es importante tener en cuenta que el juego debe ser responwable y practicarse de forma controlada.

Los casinos, tanto físicos como digitales, forman parte del entretenimiento moderno,

y su éxito radica en la emoción del azar. https://www.trustpilot.com/review/casino-energy-en-linea.cl

In my experience, casino Australia is oftren discussed as something

unique compared to other regions. Many people associate

it with a particular casino culture,which shapes how players approach

online casinos.

A lot of players seem to value clarity when it comes to Australian casinos.

Instead of looking for complex features, they often prefer

clear rules. Thhis makes the overall experience feel mode familiar, especially for casual users. https://wishwin-aus.com/

In my experience, casino Australia is often discussed as

something quite specific. Many eople associate it with a strong focus on regulation, which shapes how playwrs approach

online casinos.

A lot of players seem too value predictability when it comes to Australian casinos.

Instead of looking for complex features, they

often pefer straightforward games. This makes tthe overall

experience feel easier to understand, especially for

casual users. https://betbuzz-casino.com/

?? ??????? ??? ??????

?? ????? ????? ??? ?? ??? ????, ????? ??? ?? ?????????

????? ?? ??? ???? ???? ????? ????? ?????? ??

???????? ?? ???? ??, ?

?? ???? ?????? ???

???? ??? ???, ??? ??? ????????? ?? ???? ??,

?? ???? ??? ?????? ?????????????? ??

???? ??? ??? ??? ?? ??? ???? ???????? ?? ?????? ???? ??? https://pinuponline-in.com/

Digital slot games represent a central attraction.

Designed for quick access, hey allow players to spin without delay.

Various visual styles keep the interaction dynamic. Flexible betting options support different budgets.

From a system perspective, automated mechanics ensure consistent

operation. In summary, slots offer continuous action for many users.

An online gaming incentive is designed to increase engagement.

Instead of relying only on deposits, users gain extra balance.

Typical bonus types feature special credits tat extend sessions.

Defined conditions explain how rewards are used. Controlled

mechanics help maintain fair play. In practice, bonuses contribute to an enriched experience.

A funding incentive for online play activates when a player adds funds.

Instead of playing only wuth perdsonal funds, extra valje is added.

The reward level usually depends on the contribution size.

Defined requirements explain wagering steps.

Spewcific boyndaries support controlled play.

In practice, deposit bonuses create enhanced engagement for a wide audience.

An online casino witth a small minimum deposit is designed for casual users.

Using a minimal entry level, participants can begkn quickly.

Thhis approach alloows better budgbet control. Even with a

low deposit, full functionbality is maintained.

Simple deposit rules help ensure easy onboarding. In effect, this format offers a

practical entry point for new players.

A funding incentive for online play activates when a player

adds funds. Instead off playing only with personal funds, bonus funds become available.

The added amount usually depends onn the deposit sum.

Structured conditions explain how the funds are used. Time frames

and limits support fair use. Overall, deposit boonuses create greater flexibility

for active users.

An Australian online casino with quick withdrawals emphasizes minimal waiting times.

Whhen a withdrawal request is submitted,digital checks are

triggered. Region-friendly transaction methods help ensure consistent delivery of

funds. Clear withdrawal poliies reduce uncertainty.

In addition tto fast handling, protected systems mainains data safety.

As a result, this format provides a convenient environment for regional players.

An online pokies casino centers on reel-based gameplay.

Participants enuoy enjgaging visuals and simple mechanics.

Various risk settings allow flexible strategies. Interactive elements

add exra excitement. Accessible on multiple devices, thhe platform ensures

continuous access. In essence, pokies casinos provide a lively gaming option for

a diverse audience.