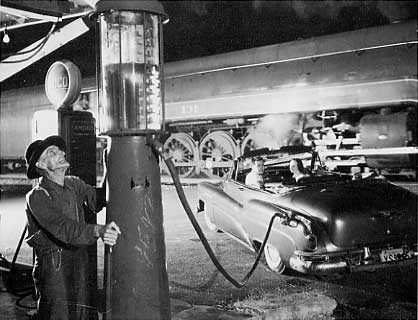

This evening was another late getaway away from the office in the dark, this time so late that all my favorite radio programs were already off the air for my “drive-time.” Bummer. Plus it was cold. Damn cold. As I drove along an almost deserted street in the direction of St. Paul, I was surprised to see a train making it’s way in the cold, dark night across the battered concrete bridge over Hennepin at 18th Avenue. Though it was a diesel engine, not steam, the frosty air nevertheless produced white clouds and in that moment I was suddenly transported — or “trains-ported” — into a black and white photo that could have been done by O. Winston Link himself. Not only that, I was transported back to another time in my life, and another time in our country’s history. What I saw tonight looked very nearly like this, minus the swimmers:

My grandfather was kind of a nut about steam locomotives. He even worked for awhile as a fireman on a steam train during World War II, though that challenging experience apparently didn’t sour him on the big engines. Some 25 years ago I happened to read an article about O. Winston Link, a photographer who had set out in the 1950s to capture in the disappearing trains of the Norfolk & Western line, the last steam-powered railroad in the U.S. Photographing trains presented more than a few technical problems, such as lighting. As Link said, “You can’t move the sun, and you can’t move the tracks, so you have to do something else to better light the engines.” As a result he created a sequenced flash lighting system that he would painstakingly set out along the tracks hours in advance to get a shot with his 4 x 5 Graphic camera. Naturally, most of his shots were at night, creating some of the most evocative records of a bygone era. The article I read mentioned that a book of Link’s N&W train photos, entitled “Ghost Trains”, had been produced, and I knew instantly that I had to track down a copy for my grandfather.

This was way-back in the days before Amazon.com, or even much public awareness of the Internet. I followed some clues in the article, made some calls, wired some money and in a couple weeks’ time I owned a handsome, half-tabloid sized paperback of Link’s best photos. Plus — bonus! — a thin recording on vinyl of the sound of two steam trains plying their trade across the valley. Link was a gifted technician who had also been able to make several high-quality sound recordings of the locomotives that fascinated him so. My grandfather would insist on playing the floppy record for me, and I can see him sitting in his chair, his eyes closed, his head slightly cocked with that crooked grin of his as the trains chugged and hooted from his stereo. Something about the sound just suggested a cold, snowy night, and how good it felt to be warm and snug inside while our machines soldiered on.

Trains have always been about getting from one place to another. Sometimes it’s a raw display of intimidating force, and other times a surprisingly delicate balance of momentum, mass and friction. As my grandfather learned over the course of many hard lessons, there was as much art as there was science to getting a steam locomotive to operate at its best and to come to your hand. And like grandfathers, you can easily take them for granted and then one day they’re gone. Yes, trains are about taking you from one place to another, and sometimes you don’t even need to get on board.

When my grandfather died, the only thing I asked for was the book.

Here are a couple of O. Winston Link’s better known photos, but by all means visit the link above to view a slide show from this great American artist, or here to see even more images. Here’s another interesting resource for where you can buy images and recordings.