by the Night Writer

600 years ago, reformist priest Jan Hus was burned at the stake by the Church. A memorial to he and his followers stands prominently in Prague’s Old Town Square.

One of our first circuits of Prague back in November came from a Hop On/Hop Off tour that took us past several impressive churches and cathedrals. The recorded narration, however, said that despite these impressive edifices, the Czech Republic is currently the most atheistic country in Europe, with just 13% of the population saying they go to church. “Therefore,” the narrator said, “most of these churches now belong, unfortunately, to history.”

Oh, but what a religious history! While Bohemia (now the Czech Republic) was part of the Holy Roman Empire since the early Middle Ages, ruled by kings and emperors appointed or sanctioned by Popes, it was at the forefront of church reform and the Bohemian Reformation, fully 100 years before Luther, Calvin and Zwingli sparked the Protestant Reformation. Czech priest Jan Hus, heavily influenced by the writings of John Wycliffe in England, was a popular and highly respected figure in Prague and he spoke, preached and wrote extensively about reforming the Church by basing doctrine and practice on scripture rather than man-made traditions, and he opposed the ethics of the Church selling indulgences and collecting fees from parishioners for nearly every function related to life and death. Among other things he wrote that the “Body of Christ” consisted of all believers and not, as held by the Church, just the Cardinals. He also preached and wrote his theological essays in the common language, rather than Latin. These and other things didn’t go over well with the Church which systematically tried to burn all of the writings of Wycliffe and Hus that it could get its hands on. When that didn’t settle things, they burned Hus; he was invited to the Council of Constance with the guarantee of safe passage from King Sigismund – and was then arrested, tried and burned at the stake for heresy 600 years ago in 1415. (When Sigismund protested these acts due to his promise of safe passage the prelates assured him that promises to heretics were non-binding). Hus was given the chance to recant and said he would do so gladly if the Council could only show him where, in scripture, he was wrong.

For political, economic and spiritual reasons however, (and because the followers that became known as the Hussites defeated five consecutive papal military crusades against them on the battlefield), Bohemia for the next 200 years was generally allowed greater freedom in its worship and doctrines (not that there weren’t periodic rounds of more burnings, beheadings, hangings and defenestrations in the name of God). The Church’s determination to rein in these reforms ultimately sparked the beginning of the Thirty Years War, which soon evolved from an authority and doctrine dispute into a geo-political maelstrom that was essentially a “World War” for the time, embroiling most of the continent and laying waste to countries, economies and dynasties. While Bohemia became, nominally, Catholic again the war essentially spelled the end of the Holy Roman Empire.

That’s my 20,000 foot summary of an intense and complex time; you can follow the links to get down to the 10,000 foot level, and spend the rest of your life trying to sort out all the repercussions and implications that continue to this day. I offer these paragraphs merely as a modicum of context for you as I roamed the cities and religious monuments of Central Europe, meditating on the past while the present surges around us in a our own maelstrom.

Esztergom Basilica pipe organ.

For example, on November 14 I sat inside the Esztergom Basilica in Hungary, looking at the marble floors, ornate walls, detailed paintings and very impressive pipe organ. It was the day after the attacks in Paris and I thought about what ISIS or the Taliban or similar group might do to this edifice if it fell into their hands. A quick historical check, however, showed that the basilica had, in fact, already been sacked by the Turks in its history – and also by other Catholic armies in the many internecine wars that have afflicted this land.

End-times cults are not new, either. The Hussites, for all their military prowess and spiritual focus, fell into internal discord. They criticized the ethics of the Church for being unscripturally focused on wealth and power, and taught that doctrine should be “sola scriptura” (scripture alone). Which lead, inevitably I suppose, to factions arguing over who was most pure. One hard-line group within the Hussites saw their purpose as to hasten the return of Christ, by bloodshed if necessary, and took their name – the Taborites – from Mt. Tabor, described in scripture as the place where Jesus will appear.What we see is that doctrine – Catholic or Protestant – is often an imperfect prism of truth. We may grasp a profound truth that, in the greater scheme of things, is relatively no bigger than the jawbone of an ass, but in our hands becomes a cudgel.

A line from the sacred text comes to mind: “What can man do in the face of such reckless hate?” (That text was from the “The Two Towers”, and yes, I know, that was how it appeared in the screenplay, not the book. No fatwas, please.) The question is valid for at least the last 600 years, and no, I’m not making a moral equivalency argument. There is no such thing as “moral equivalency”: you’ve either taken on the nature of Christ or you haven’t. All other measurements on any scale you (or I) come up with are ultimately meaningless. Still, the idea that people could somehow see God glorified by the heinous death of others is so profoundly twisted that to me it can only be proof of a Devil and not, as the humanists might say, proof that there is no God. What part of the Son of God dying for Man requires making other men die violently for God? What part of being transformed by the renewing of my mind implies forcibly conforming others? I don’t think I could, now, personally take up arms or do violence to others simply because they thought differently or sinned differently from me.

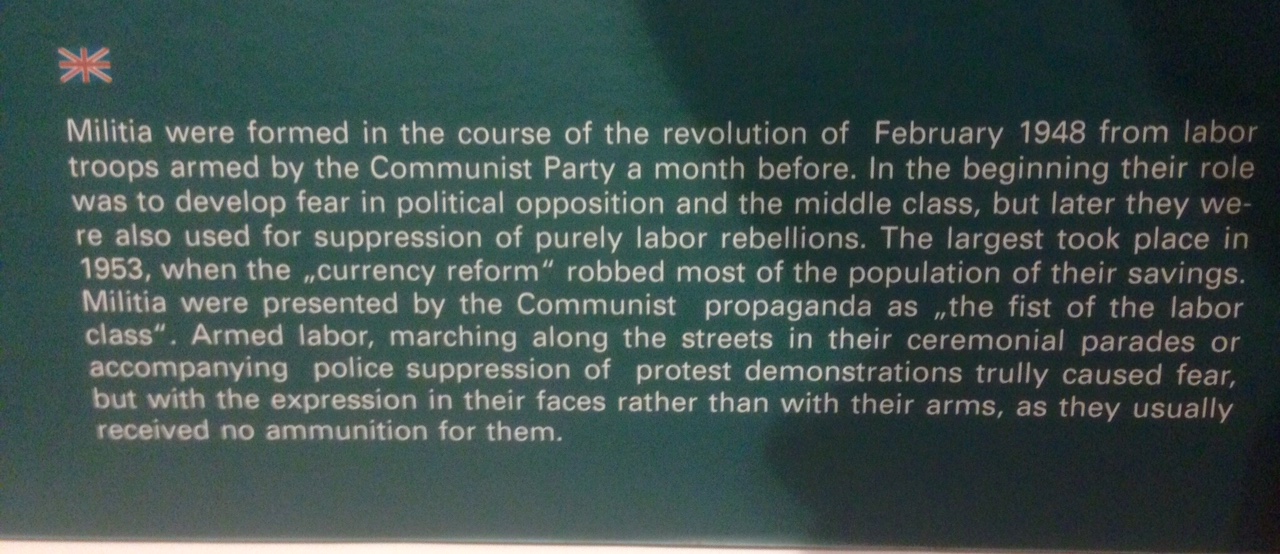

But could I, would I, if the other was trying to harm me? I don’t know. My religious freedom is dear to me – and has cost others dearly. The desire for freedom is strong in humans, as strong as the human desire to dominate others. I know the anger and sorrow that I felt in watching the film clips of the Soviet troops and secret police falling upon the Czech students in 1968. Could I have remained quiet if I had been there in those days? Could I have stilled my heart and thoughts to try and hear from God what He wanted me to do, or would I have rushed forward in righteous outrage, hoping that was the right answer?

I believe that the desire for freedom is something God has placed inside us. Even the Czechs, oppressed in the 20th century first by the Nazis (who offered a twisted God) and then the Communists (who insisted and taught that there isn’t a God), could not have the desire for freedom beat or squeezed out of them. And from a certain perspective, I can understand their supposed atheism today. For all their beautiful churches and illustrious history, they may be justified, after the last 80 years, in being suspicious of anyone or anything that wants to tell them the “right” way to think. After being ignored, then betrayed and then bombed by the Christian West and then oppressed by the God-less, they could wonder why they should think about God when He doesn’t appear to be thinking of them. The beautiful churches must seem like the living room full of nice furniture and precious objects I wasn’t allowed to go into when I was a kid (nor did I deserve to). They desire freedom, and no doubt would like to see what that looks like – how can our lives demonstrate that?

The fact is, however, we all have “reasonable” reasons to doubt God exists, whether we’ve been oppressed by totalitarian regimes or not. Ultimately, it wasn’t theory or doctrine or a church building that proved His existence to me, but seeing His word made true and coming alive through others and in my life. Touring the cathedrals and basilicas I was reminded of a teaching from a few years ago: God moves, and the move becomes a Movement. The Movement becomes a Monument to what God has done, but also an excuse to focus on the monument rather than continuing to stay tuned to the Move. Ultimately, the human result is that the Monument becomes a Mausoleum. The people of the Czech Republic – or our neighbors – aren’t going to know God is real just because of a church building, but by our lives and the way we reflect His love. Ultimately, He’s not looking for a church as much as He is looking for us to be the Church.

To go any further with my reflections and what those meant to me in Prague I’d need to bring things from the 20,000 or 10,000 foot level down to the 100 foot level. I’m not going to do that now, but I will in a later post. (Yes, I believe I’ll keep the doors open here at the blog for at least a little while longer). For now, let me leave you with two things.

First, as we discussed the history of revelation, revolution, oppression, and – hopefully – more revelation, a particular hymn came to mind. Tiger Lilly could also feel it, and agreed to sing the hymn a cappella (which, coincidentally, means “in the manner of the chapel” in Italian) for our church back home and this blog. See the link below.

Finally, it seems appropriate to leave you for now with the words of Jan Hus, inscribed on his monument, and taken from his last letter to his followers:

“Love each other and wish the truth to everyone.”

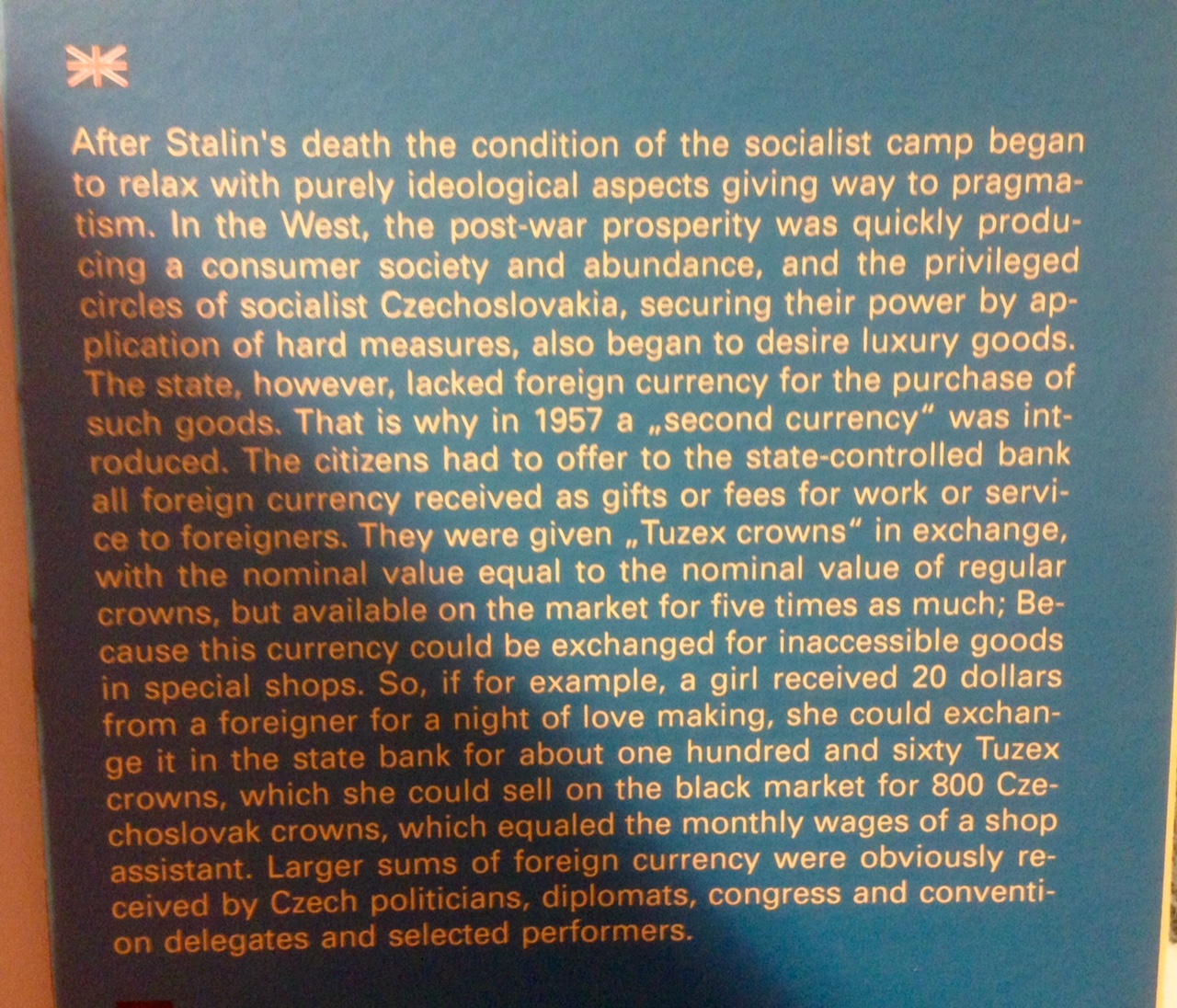

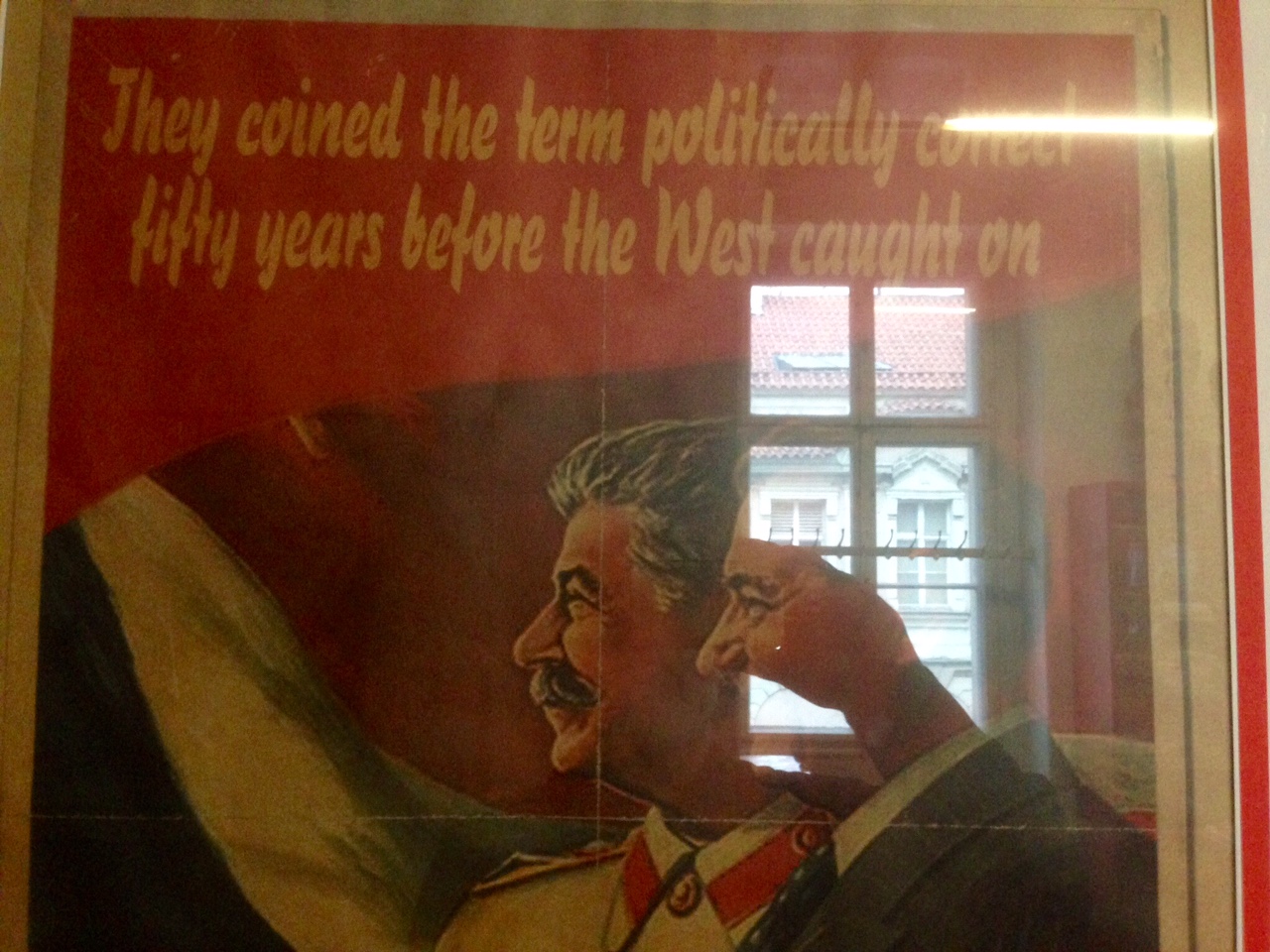

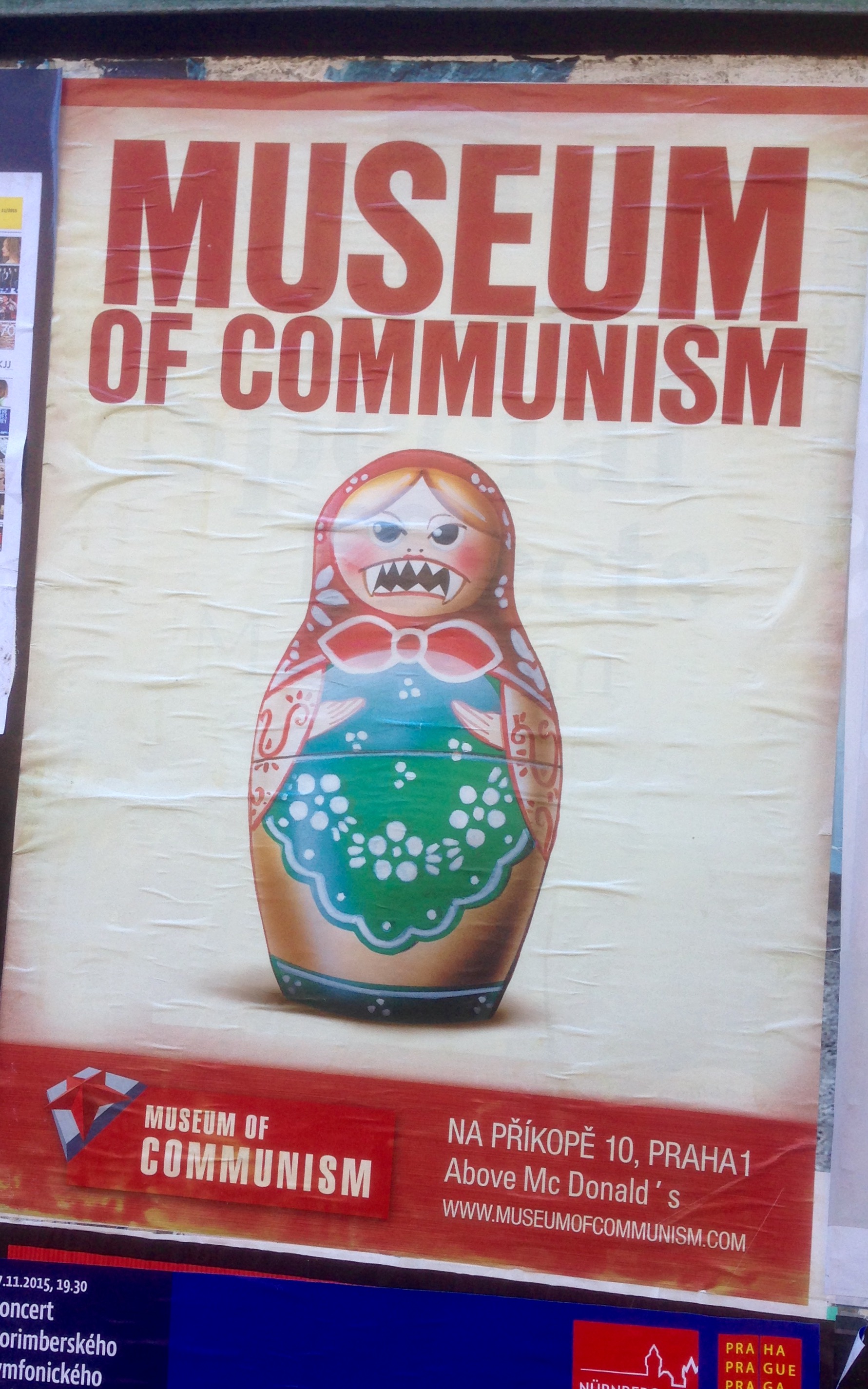

I saw this museum advertised the first day we were in Prague and made a note to see it while we were here. I loved the poster, for one thing. It came down to our last weekend and I realized we still needed to go, so we set out. I have to say it is one of the most affecting places I’ve visited over here.

I saw this museum advertised the first day we were in Prague and made a note to see it while we were here. I loved the poster, for one thing. It came down to our last weekend and I realized we still needed to go, so we set out. I have to say it is one of the most affecting places I’ve visited over here.